Greater New York 2010

MoMA PS1 Contemporary Art Center

Long Island City, Queens, NYC

May 23 – October 18, 2010

PS1 Celebrates the Presence of the Artist

May 24, 2010. Now is the Spring of our discontent, marked by downward stock market volatility and a continuing Gulf oil spill. But as the Whitney Biennial enters its final week, our critical fancy turns to thoughts of Greater New York. The newest blockbuster in town, with a mission to present the best young and underknown art that our city has nurtured over the past five years, GNY is now in its “third iteration”. Previous editions were mounted in 2000 and 2005 in what is rather grandly called the MoMA PS1 Contemporary Art Center. Those who keep track of such things will note a change in the order of the institutional names – MoMA now stands predominate – indicating that the bride has finally been subsumed by her bachelor, even. Vita brevis, but Ars museums go on longa and longa. Hence the stated “quinquennial” timing of the exhibition, a designation that only a dedicated builder of dynasties could love.

Like the Biennial, GNY has been drastically downsized from over 200 participants in 2005 to the current roster of 68 artists or artist groups. This reduction, to one third its former girth, might lead some wags to call it “The Lesser of Three Greaters” or more simply “The Lesser Greater”. It is, of course, a direct response to the economic recession and pruned museum budgets. But it also feels like the three curators – Klaus Biesenbach (PS1 Director and MoMA Chief Curator at Large), Connie Butler (MoMA Chief Curator of Drawings) and Neville Wakefield (PS1 Senior Curatorial Advisor) – hope to achieve a pared down elegance within the necessary limitation of means, a “less is more” transcendence that turns away from the glut and gloss of previous flirtations with an engorged marketplace. Gone are the days when MFA candidates with a certain buzz could sell out their thesis exhibitions, even before graduation, and then find early career support in a vast survey show organized by an obliging non-profit space.

The new austerity hopes to embrace a clearer, more cohesive vision, allowing the curators to collaborate closely with a smaller pool of artists to achieve a detailed, nuanced presentation of the work, including room-sized installations and other intensive efforts. At least this is the party line of the new, post-Alanna regime. During the press opening, Biesenbach noted that while PS1 does not have that much money, it simply wallows in space. An obvious way to utilize this, aside from filling all four floors with video, installation, photography, sculpture, digital/new media, and painting (listed in loosely descending order of their inclusion in GNY 2010), is to promote a dense schedule of performances, rehearsals and other artistic interventions. As the title of Marina Abramovic’s exhibition at MoMA suggests, it’s all about the artist being present. Encouraging the heady atmosphere of an art club, in situ, could merge with the annual Warm-Up DJ bacchanalia to make this a PS1-centric summer.

GNY would like to be a watershed effort that gathers lots of contemporary production under one banner and gives it a “zeitgeist” spin, even if the press release only blandly claims that it “centers largely on the process of creation and the generative nature of the artist’s studio and practice.”

The difference this year involves several initiatives that would return PS1 to its original experimental, “project space” status from the 1970s. A number of artists were given early access to produce on-site work, including Franklin Evans‘s taped up studio-in-a-room installation and Kalup Linzy‘s overwrought black gay soap opera tropes. Others have established “open studios” with selected public viewing hours: dance/performance duo robbinschilds and performance/process sculptor Ei Arakawa. Aki Sasamoto (also in the Biennial) invited Saul Melman to join in her basement mosquito-zapping installation; he is slowly applying gold leaf to the ancient boiler that heated the original school building. There is a “rotating gallery” organized by a panel of guest curators that will change exhibitions every five weeks, and a “5 Year Review” room that charts the aesthetic history of NYC over the last half decade.

All of this, including the extensive performance calendar, could make the current GNY more interactive, more touchy-feely, akin to the celebrated tale of the elephant and the blind men. Depending on when and where you approach it, at which time and from what specific angle, GNY could morph from tree to snake to wall to fan.

A case in point. During the Sunday afternoon opening, Terence Koh (Biesenbach’s axiom of performance, right after Marina Abramovic) reprised an abridged version of his glossolalia/art history slide lecture from Performa 2009. It was hilarious, brilliant, over-the-top. But it will not be repeated, so unless you were there, it was not part of your direct GNY experience. (I say “direct” because it was recorded by many cameras and will probably be online soon.)

Like the Biennial, which included a majority of women for the first time ever, GNY 2010 is no slouch, with 43% female participation. There is also some overlap between the rosters of the two exhibitions, among both male and female artists. This might indicate a certain curatorial “tradition of quality” that cuts across institutional lines, recognizing both the growing importance of women and also the parameters of excellence throughout. But when I asked Butler whether the three headed structure had been a “seamless” experience, she indicated it was anything but. One can imagine the major protagonists, each armed with their pet projects, favorite artists, amendments and methods of working, submitting to the review of their peers, stirring it up in an amiable cauldron of research, dialog, and dissent, with the final veto reserved to Big Daddy Biesenbach. This process could lead to an energized dialectic, the push-pull creating a livelier, more challenging exhibition than might be possible from a single tendentious viewpoint. So there are blandishments as well as pitfalls to curation by committee.

But enough of this meta- conjecture. Here, in no particular order, is a selective overview of the artists and the work at GNY 2010.

David Brooks. The Duplex Gallery at PS1, with both first floor and basement access, often provides a good barometer of the institution’s intentions, and is generally reserved for large scale, signature work. Preserved Forest, a massive installation incorporating tropical trees, earth and concrete, is a brutalist earthwork, constructed indoors, that invokes the dystopia of Amazon deforestation, coating the leaves and stems with the dusty, deathly smear of “progress”. It feels appropriate to a moment when we are all balefully watching an inexorable oil spill. Brooks has noted that the production of concrete is responsible for ten percent of worldwide CO2 emissions, adding to the cautionary ecological statement. He presents a physical tension, a visible strain between nature and industry, that hints at the huge expenditures of energy required for their coexistence. This recalls the entropic concerns of Robert Smithson and other Earthworks artists.

Brooks accessed a similar vocabulary of materials at his recent Museum 52 show, a poured concrete piece with the paving slabs of an interior sidewalk lifted up by a series of hoists and chains. The last slab also contained an uprooted tree, which defied gravity as it fought for its ungainly stasis under the skylight.

Tommy Hartung is one of five GNY artists who show with Candice Madey’s On Stellar Rays gallery in the Lower East Side (the others: Debo Eilers, Zipora Fried, Brody Condon and Maria Petschnig). He is a filmmaker and stop-action animator who deconstructs the formalism of the medium with gnarly props and purposely archaic or proto-cinematic effects, editing found footage together with his own shots. A bricoleur who compresses and reassembles elements from scientific or anthropological films (the great white hunter on safari, the ascent of man), he manages to subvert their original purpose.

Hartung locates a devolved, convoluted narrative in his faux documentaries that undercuts the usual sunny, progressive tone of educational films. One of his pieces at GNY is essentially a prop, an aquarium containing two tropical fish backed by color reproductions of framed old master portraits. It’s that old world-in-a-fishbowl metaphor again. The two pet koi become iconic stand-ins for the museum audience, swimming about, popping their eyes, looking for aesthetic sustenance. Apparently Hartung plans to visit them regularly and make the requisite feedings.

David Adamo is showing whittled down canes and other wooden implements, with the resultant shavings, at the Whitney. At GNY he ups the slapstick and the sublimated aggression with rows of neatly arranged (head-to-tail, tail-to-head) Louisville Sluggers that cover the entire floor of the gallery like the residue of some demented lumberjack. (James Kalm http://post.thing.net/node/3051 notes that the bats seem to be “factory seconds”. They have visible flaws in the grain and are unvarnished. The wood will darken over time with shoe scuffs.) It is a humorous commentary on the mock heroics and macho posturings of Minimalism and Carl Andre. But having us walk on the bats also keeps us off balance and challenges our progress through the room, an aside on the brittle mechanics of performance art. Adamo is interested in how slight alterations to simple, everyday things can imbue them with resonance as fetish objects or ghostly remainders, revealing some of the conceptual baggage of the readymade. His arrangement of work in pared-down, monastic spaces embraces the scatter of post performance detritus.

Speaking of lumberjacks, transgender artist Leidy Churchman, one of the few painters in the show, executes flat, colorful, modestly scaled figurative work on wood panels, often depicting homoerotic encounters in the woods among hirsute, flannel shirted men. Despite the outre content of casual anal sex, dangling strap-on penises, and possibly even snap-on beards, there is a playful, non-threatening amicability about the work, due perhaps to its humble folk art antecedents. Churchman’s paintings reside on the continuum between Alex Katz, John Wesley and Dorothy Iannone (the Pop Art referents) and early American woodcraft. Curiosity about the polymorphous perverse as an ongoing theater for experimentation is further emphasized by a table of carved wooden butt plugs and an accompanying video that prods a nude, prone body – as if it were on an operating table – with thick globs of paint and other prosthetic additions.

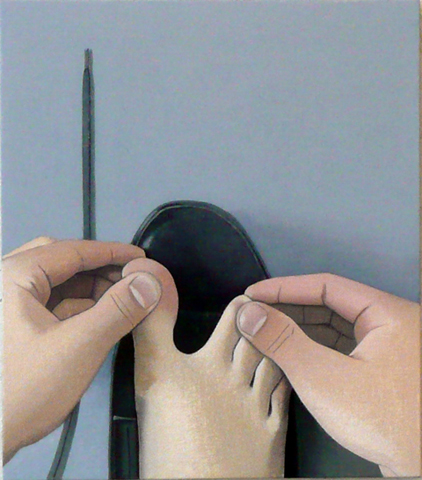

Other painters worth noting: Tauba Auerbach‘s geometric fold in/fold outs; Caleb Considine‘s ectoplasmic reveries (like the spooky fungal toe inspection above); and Zak Prekop‘s tactile, ridged, gestural abstractions.

Video is the predominant medium at GNY. For better or worse, it is the great workhorse of many contemporary artists, often combined with other media. Two of the more memorable video inflected installations that dot GNY are by Ryan McNamara and Sharon Hayes. McNamara seems to approach dance as a vehicle for his personal exorcism. His two channel work (made in 2008 and already part of the MoMA collection) shows him performing a “zombie booty dance” (as described elsewhere) both outdoors on a country road and against a red curtained theater proscenium (see the image at the top of this posting.) McNamara plays a go go boy with an apparent history of drug abuse, and while he boogies down to a pop dance number rather than to the anthemic “I Can’t Stand Up For Falling Down”, he seems in constant danger of dropping to the floor in a catatonic, loose-limbed stupor. The video is supplemented by Make Ryan a Dancer, a performance taking place all over PS1 at different times and places, in which visiting professional dance instructors will attempt to hone McNamara’s “movement art” skills, using a portable mirror and ballet barre.

Then there is the five channel video of Hayes, who restages her LGBT political rally, Revolutionary Love, that was commissioned by Creative Time and originally shown as part of their Democracy in America project at the Park Avenue Armory. Accessorized with balloons, flyers, streamers and other political ephemera, it documents the gay rights street performances that she staged opposite the 2008 Democratic and Republican National Conventions in Denver and Minneapolis. PS1 devotes the entirety of their third floor Great Hall to the this exercise in sincere, grass roots agitprop.

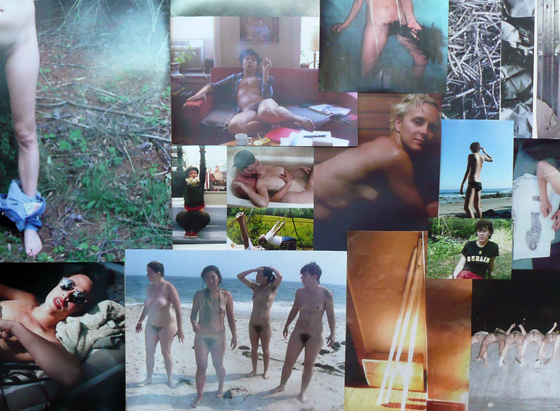

A.L. Steiner produces one of two sexually explicit and transgressive rooms that PS1 felt required a printed advisory. Angry, Articulate, Inevitable, her floor-to-ceiling collage, on two walls, of C-print photos, laser inkjet prints and photocopies, is a celebratory mash up of girls on girls on girls, many of them naked and all of them obviously in love with each other: a fierce, proud, in-your-face ode to dyke consciousness.

Leigh Ledare, on the other hand, tends to orient his sexual adventurism within the family, using his demonstrative mom as the prime subject for his camera. The three pieces seen above, called Mother With Scepter, Untitled (Fucker), and Me and Mom in Mirror, give a fair indication of his exhibitionist concerns. Friends from the demimonde also pose for photos – a la Nan Goldin – as does Ledare himself. My favorite shot has him looking mischievously back at us, over his shoulder. He seems to be pissing against the wall between a Cindy Sherman photo and a Chris Wool painting owned by art consultant Thea Westreich. (Shades of Pollock and Peggy Guggenheim!)

Institutional darlings The Bruce High Quality Foundation, also at the Whitney Biennial with their We Like America and America Likes Us video tone poem emanating from Joseph Beuys’ ambulance, contribute a room of sleek white pedestals to GNY. Possibly referencing Scott Burton’s 1989 Artist Choice exhibition at MoMA of Brancusi’s sculptural pedestals or the National Holocaust Memorial, the Bruce’s Perpetual Monument to Students of Art continues the pedagogical orientation of their BHQF University, offering the pristine white pedestals to art schools in exchange for old, used, scuffed up models. It is an ongoing exchange program that, over the course of the exhibition, should change the room from ultra white to dingy, decrepit and scarred by the marks of history. While the gesture is essentially philanthropic, the sardonic Bruces also seem to be demonstrating how readily a patina of authenticity can be acquired, and how historical legitimacy can be feigned through subtle alterations.

[In a bit of institutional gate crashing, an unknown artist already “altered” some of the Bruce pedestals, and many other horizontal surfaces at PS1, by placing little plastic baggies on them, filled with a mysterious black powder and inscribed with the text “i remember you from the future .. time and space died yesterday”. To that guerrilla artist: Feel free to comment on this site if you have anything to add.]

It seems I’ve barely scratched the surface. Lots of other work in GNY should be mentioned, but one has to stop somewhere. So in conclusion, allow me to briefly cite five more artists well worth your consideration.

Hank Willis Thomas displays his entire Unbranded: Reflections in Black by Corporate America 1968-2008 series, forty-one years of images culled from commercial advertising in magazines that chronicle the changing faces of blackness fed to America on both sides of the divide: from Ebony, Jet and Essense to Vanity Fair and Sports Illustrated, from kids enjoying Coca Cola on their stoop to Whoopi Goldberg as a nun, from several gravity defying Afros to Dennis Rodman’s buff torso and white upper lip (from the “Got Milk?” campaign). But Unbranded hardly wallows in the safe nostalgia of consumer camp. By removing all text, logos and product names, Thomas advances a stringent semiology of racial signifiers which reminds us that black bodies have generally been recruited for their commercial value, whether under the plantation feudalism of the antebellum South or the media saturation of global capitalism.

Rashaad Newsome‘s two part video projection combines rapid fire editing of images from hip hop music (playas, hos, Benjamins and bling), scored to a funked up version of elegiac chorale music from Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana, with added DJ beats and scratches. It is a stunning, hypnotic conflation of the sacred and the profane, a lesson in how urban myths become encoded and transmitted, and how they can bust out larger than life. Newsome has examined these codes before; his video in the Biennial deconstructs the gestural “language” of voguing.

Naama Tsabar is a sculptor and installation artist who not only plays in a band but uses the hardware of rock music to construct her pieces. Doublecherryburst is two Gibson Les Paul guitars joined at the head, or rather sharing a common headstock; it can actually be played. She also constructed a room sized installation of a drum kit sitting on a gigantic jewel box, and wrapped a performance stage, fully loaded with amps, monitors, guitars and mic stands, in black gaffers tape. This work places her on a continuum with artists like Christian Marclay and Banks Violette. For GNY, she produced two walls, constructed from bookshelf speakers, backed with guitar strings that have been stretched over electric pickups. The walls can be plucked and strummed by the audience, and they resound quite loudly.

Brian O’Connell contributes a subtle intervention in the small gallery-within-a-gallery on the second floor that was built for PS1’s previous 1969 show to restage a MoMA exhibition of LA light artists Larry Bell, Ron Davis, Robert Irwin, John McCracken and Craig Kauffman (who recently passed away). Now, in a fitting homage to strategies of the ineffable and to architectural interventions that explore the dialectic of presence/absence, O’Connell wraps the columns in a squared-off packing of rammed earth, an amalgamation of potting soil and cement that “squares the circle” of the original rounded structure. It already looks like it’s always been there.

Finally, a star is born. Liz Magic Laser has received considerable attention for her work at GNY. Collaborating with the Da Vinci Surgical System, makers of a robotic device, Laser shot a video in which her pocketbook and its contents – driver’s license, dollar bills, wallet, cosmetics, the very fabric of the bag – are pulled, prodded, cut up, violated. Andrew Jackson’s face is snipped right off the twenty, while other miniaturized atrocities are suffered by hapless objects that somehow manage to acquire a pathetic patina of suffering.

Lazer calls the piece Mine, a pun which refers both to the process of physical excavation from the purse/mineshaft and the very real intrusive threat to private property and identity. Is she restaging a medieval morality play, casting the objects in her purse as Every(wo)man and testing our unquestioned faith in the benign face of progress? The object world is anthropomorphized, the human world given an objective correlative. The actual pocketbook sits in a nearby vitrine, looking like a victim of domestic violence.

This is one of the more insidiously transgressive pieces in Greater New York. But even considering the possibility of controversy engendered by some of the artwork, it still promises to be a fairly cozy summer at PS1. The pervasive hothouse vibe – of artists in residence, works in progress, performances popping up in every corner, open studios, colloquia and collaborations – could even lead to a hushed rendition of “Kumbaya” around the James Turrell skylight. The ascendancy of social sculpture qua performance and video qua performance is the norm under PS1’s new management. Now that it’s the Haus of Klaus, networking is king and the ineffable “presence” of the artist is seemingly just as important as the actual production of a body of work.