For a show centered on the early, punk-inspired work of graphic artist Raymond Pettibon, the Schmidt Center Gallery at Florida Atlantic University has been tricked out in a style that pays tribute to the willful disorder of old school punk clubs of the late ’70s. The effect is approximate–posters and flyers litter the walls but no blood or alcohol spatters the floor. Still, the spirit is there, lively and diverse.

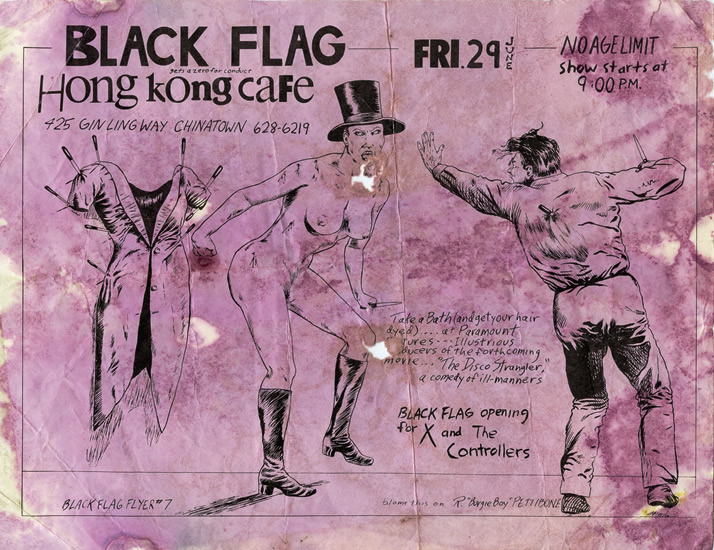

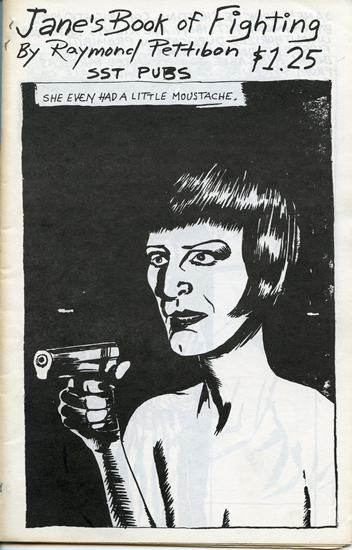

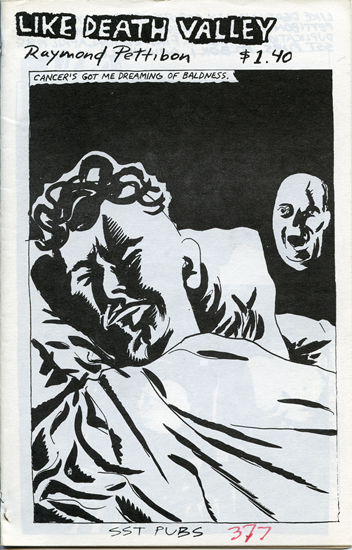

The heart of the show is “Raymond Pettibon: The Punk Years, 1978-86,” a traveling exhibition of more than 200 flyers, posters and album covers created for punk bands of that era—chiefly Black Flag and other Los Angeles bands at the center of the early Southern California scene—as well as early artist books like “Console, Heal, or Depict” or the “Tripping Corpse” series.

But the show also includes a selection of Pettibon’s more recent work, on loan from South Florida collectors, contrasting Pettibon’s origins with his later rise to fame within the world of high art. There is also a series of musical events, films and lectures, as well as a collection of vintage punk ephemera, chiefly zines and posters, from South Florida and Tampa.

The punk aesthetic that developed in Southern California in the ’70s was fiercely juvenile, the controlled temper tantrum of young people who had decided the American Dream was a ruse. A preceding counterculture had failed to dethrone the capitalist empire, and punk anger was directed as much against the hippies as it was against “The Man.” Nihilism displaced Peace and Love.

The scatological impulse was a key feature of this youth rebellion, and there was a defiant messiness to the music’s sound, the performers’ style and the movement’s venues of choice—typically the dirtiest, grungiest clubs in the most questionable neighborhoods. That a virtue was made of poverty played a role in this: Unemployed or working at the 7-11, who could afford high-grade sound equipment, fancy costumes, or the rents of established clubs?

That Pettibon was not schooled as an artist was consistent with the scene’s belief in inspired amateurism. A graffiti’d artist statement explains: There was the idea you could do it yourself, that you didn’t have to have Warner Brothers behind you or you were going to sink into nothingness.

But Pettibon’s medium was free of poverty’s constraints. There was only so much one could spend on pen and ink, and he used those tools to appropriate and mock stereotypical American figures and gestures, drawing heavily on references from mass culture. Pettibon’s abrasive graphics, with their caustic snippets of text, were a perfect fit for the “faster louder” sound and angry lyrics of the punk bands.

Much of the work resembles single-image cartoon panels, and owes a debt to Marvel Comics, if not Roy Lichtenstein. Drawn almost exclusively in black and white, images of violence predominate: scissors, knives, guns, a chain saw. The body is shown in danger, cornered or under assault—by authority figures, lovers, oneself. There is sex, too, but tinged with despair and alienation.

What emerges, however, is that while Pettibon’s work was a significant part of original punk culture, the common ground was one of content rather than style. While conflict and disorder were virtues in the aesthetic of punk and what went on to become punk’s hardcore wing, Pettibon’s strengths were his precise line and taut imagery. The area of agreement was the acerbic commentary on contemporary culture and mores.

Hardcore punk continues to this day, just one of the varied aesthetic and lifestyle choices on offer in the superstore of American life. Like the others–born-again, stoner, biker, Tea Party patriot, etc.–it has its devotees and diehards, each of whom swears that theirs is the One True Faith. Pettibon, meanwhile, ascended to art world stardom.

By the ’90s, Pettibon was a regular at the Whitney Biennial. In the new millennium he has been feted throughout Europe and in Japan. Currently he is represented by David Zwirner, the prestigious New York gallery, as well as galleries in L.A. and London.

The Schmidt’s selection of later Pettibon comes from the Rubell Family Collection in Miami and Burt Minkoff, a Lake Worth collector. It only extends into the ’90s, and while it shows some development it reveals no radical departure from the early work. The line is thickened, there is more use of color, the accompanying texts include the occasional reach toward more elaborately poetic language. In some, the figures are more supple, and the command of anatomy is stronger.

In Pettibon’s most recent work, on the other hand, there is a striking new emphasis on the whole field of composition, so that works exist as a totality rather than mere figures and background. There is also a growing tendency towards abstraction. Lacking pieces from this stage of his career, however, the viewer may think Pettibon struck treasure early and mined it no deeper.

There is some irony in that Pettibon rose up from within an avowedly anti-hierarchical subculture. But his current stature seems an inevitable development for an artist with such mastery of form and such a well-defined vision. The greater irony is that the punk scene generally, founded on a most anti-authoritarian impulse, with an ethic of “live fast, die young and leave a good-looking corpse,” would eventually be the subject of veneration and Ph.D. Theses.

For those who were there, it has a bittersweet taste.

The Schmidt Center Gallery is located on the FAU campus in Boca Raton. The Pettibon show runs through Jan. 22.

Punk tribute musical performances are scheduled for Jan. 14 (FAU Punk KÖLLEKTIV, a student group), 21 (Bladesong) and 22 (School of Rock, Coral Springs), all at 6 p.m.

A lecture by FAU graphics professor Eric Landes, “Cut & Paste: Typography, Violence & the Punk Rock Aesthetic,” is scheduled for Jan. 20 at 7 p.m.

Film and director’s appearances by renegade independent documentarian Bill Daniel are scheduled for Jan. 18 at 7 p.m. (“Sonic Orphans”) and Jan. 19 at 1 p.m. (“Who is Bozo Texino?”)

Daily film and video screenings running the length of the show include 1978’s “Louder Faster Stronger,” shot at S.F. punk mecca Mabuhay Gardens, cult classic “Desperate Teenage Lovedolls” (1984) and a number of films from skatepunk documentarian Stacey Peralta.

More information on the gallery and the Pettibon show here:

http://www.fau.edu/galleries/RPettibon.php

More detailed schedule of events here: