“Do we live in an age of panicky materialism?

On a muscle beach in California, it wouldn’t have caught my eye. But the following incident recently happened in the toilets of a bar in Malmö, Sweden. This guy walks in, sees himself in the mirror above the sink, pulls up his top, stares and smiles the most blissful smile. I swear the look of love was in his eyes. He didn’t see me and I couldn’t see what he saw in the mirror, but I assume it was abs. His abs. I later spotted him with his date at the bar. He looked happy, but not as thrilled as he did when he pulled up his top to reassure himself of what he had. Now: what do you have?

Me, I’ve got anxieties. And I feel I am not the only one. I live in Berlin, and when time comes around again for the local Art Week or Gallery Weekend, one can sense the fear rising. People pray for collectors to bring money to this relatively poor city like one summons rain to save the crops. To attract the money, big events are set up where people amass to await the cloudburst. Meanwhile, in the galleries, art works designed to look as instantly alluring as the latest high-res touch screens are gently sobbing ‘see me, feel me, touch me, own me …’

On the academic circuit, people get anxious too: knowledge is capital – if you can prove you have it. But how are artists to prove they have ‘artistic knowledge’ when no one knows what exactly that is supposed to be? To help certify their elusive competence, universities now offer artists a PhD: a medal for bravery in the field of artistic research. If it’s yours, it’s yours. You should be safe when winter comes. And winter is coming: student loans have to be re-paid, landlords raise rents, governments cut arts funding and cities hand bohemian parts of town over to people who actually have money and don’t just go around being creative. So you’d better have your high-res art product ready to hit the market, or a key to the door of the education sector.

In his new book, Neomaterialism (2013), Joshua Simon perceptively argues that debt is the crux of the matter. Credit-card purchases and mortgage settlements may feel abstract at first. But debt brings its material truth home to you: you do not own that new computer, tv, car or flat; they own you. As long as you cannot pay back the debt, these things put a spell on you: you are theirs. So material values today translate straight into material fears. And who could stay calm? When housing bubbles burst overnight, you want something tangible to hold on to. Be it abs. Be it sales. Be it tenure.

The rule of panicky materialism urgently requires the kind of Marxist analysis that Simon develops. Arguably, however, it is precisely the firm denial of the panic politics governing material affairs today that has bolstered the slow but steady rise of ‘speculative realism’. As advanced by its most prominent spokesperson, Graham Harman, this philosophical trend promises to restabilize the positivist faith in a rock bottom of material reality – Harman promotes ‘object-oriented philosophy’ as the long awaited ‘revival of metaphysics’. The big boys are back in town and aren’t we glad! It speaks volumes when Harman, in his 2010 book Towards Speculative Realism, praises the ‘admirable realism of the military’ as a good example of object orientation. It is equally bizarre to read him describe the ‘volcanic core of objects’ as a ‘witch’s cauldron’ or ‘alchemist’s flask’ but still insist this had ‘nothing to do with a possible panpsychism of fire-souls and oxygen-spirits’. In the tone of such denials, I cannot help but hear the imperial voice of a scientist in a haunted house declaring ‘there must be a perfectly rational explanation for all of this’ while levitating furniture spins around his head.

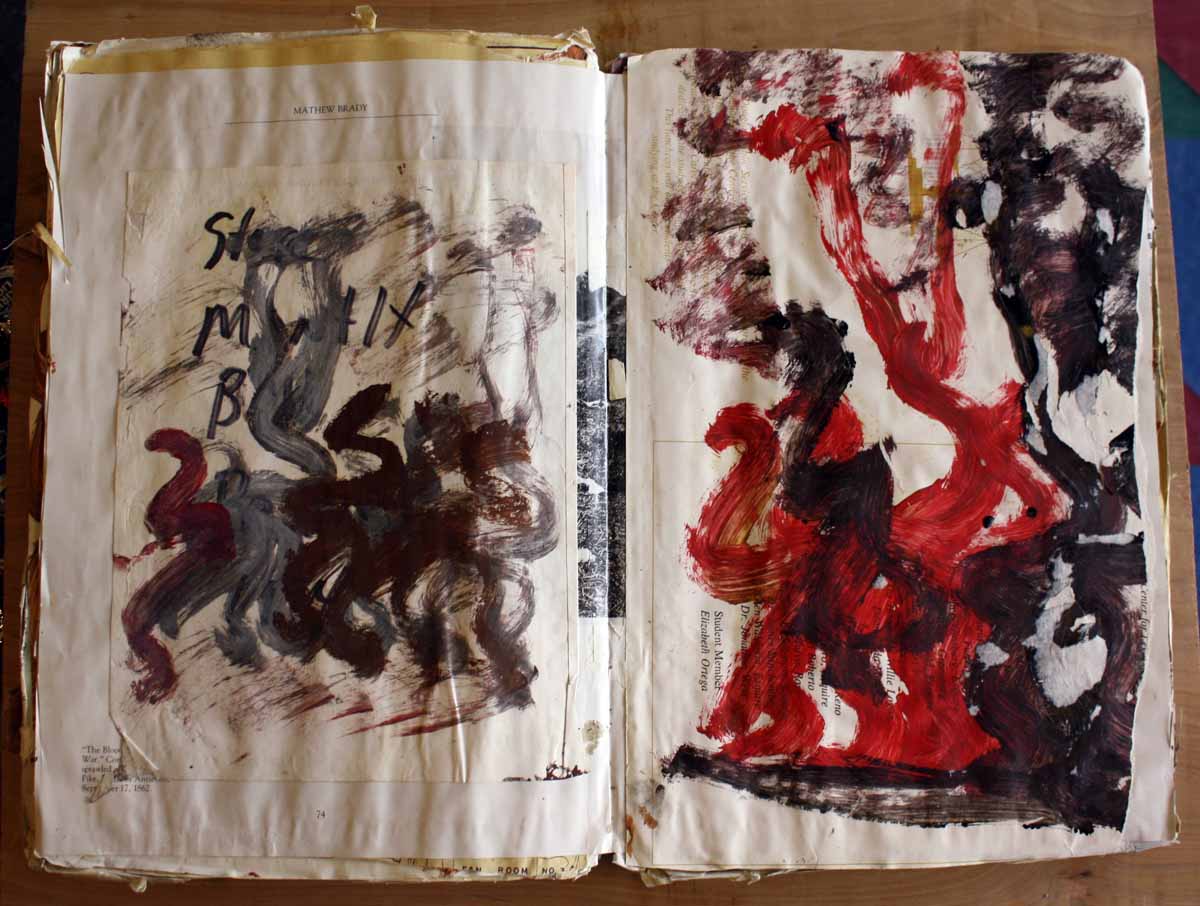

Personally, if I were to support a revival, it would be that of the resurgence of interest in art historian Aby Warburg. The renewed currency of his thinking seems to stem from the fact that Warburg was courageous enough to link practices in modern material culture back to animist rites. In his 1923 reflections on ‘Images from the Region of the Pueblo Indians in North America’, he admits that a tribal snake dance meant to bring rain, a Renaissance work of art seeking to capture beauty, and his own library compiled to grasp the secret of human culture, may have something crucial in common: they are all material efforts to engage the evanescent forces which shape our fate. As citizens of the modern world, we remain subject to the same sense of terror that animist rites address when they assume that matter has soul, and that devils live in all things playing cruel games with us. In a world of debt, where the things you own possess you, the only true realism may well be speculative animism.

So, could we fight material fear with animist means? Dance with snakes to bring the rain? Success won’t be guaranteed. But, if performed consciously and collectively, the dance would at least help to acknowledge fear as a common condition. Panicky materialism holds people in solitary confinement; career survival is about your muscle show and yours only, so it seems. Which is bizarre. Experience indicates that it takes interpersonal alchemy to cultivate environments in which artistic practices, reflective thinking and human relations flourish. Working such environmental magic is quite an undertaking, both materially and spiritually. But it’s not a question of metaphysics – perhaps it’s just a matter of looking around to see if you’ve got company. In the toilets or elsewhere. You usually do.

Jan Verwoert”

(Via Frieze Magazine.)