Tom Sachs

Space Program: Mars

Park Avenue Armory

66th Street and Park Avenue

produced by the Armory and Creative Time

May 16 – June 17, 2012

May 16, 2012.

It must be a daunting task for any artist to consider placing a body of work into a huge, cavernous void such as the Park Avenue Armory. How to fill the 55,000 square foot Drill Hall, with its high vaulted ceilings and acres of plank floor, in addition to the ornate, memorabilia filled, wood paneled corridors and regimental meeting rooms, and not have your work overwhelmed by the vastness? How to signify amid the hangings, accoutrements and sheer volume of another age?

It takes a lot of gumption to even consider tackling such a vast space with a project that will properly connote, both to an “inside” art world audience and also to the general public, that will not get lost in the deep fissures of physical and metaphorical stowage. The challenge is to provide sufficient entertainment value and spectacle to justify the prerogatives of the venue without watering down the meaning or pandering to LCD taste.

A previous artist entrusted with the Armory, the Brasilian Ernesto Neto, responded with long, sinuous drapes of Lycra fabric and encased tendrils of spice pods, both buttressed from the floor and hanging from the rafters. Another artist, Aaron Young, hired a motorcycle gang to do wheelies, to mark the floor with skids that created a multi-paneled painting.

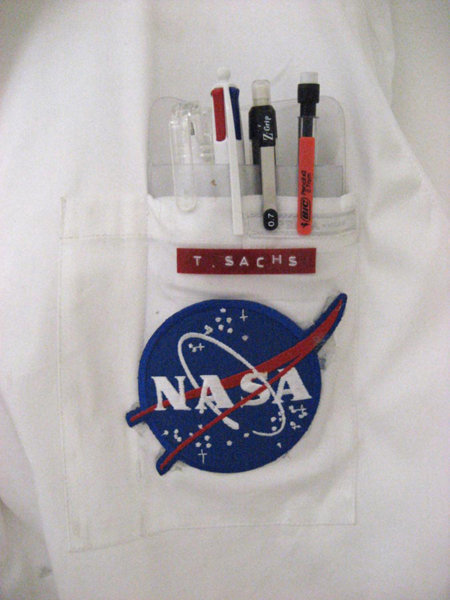

Tom Sachs has addressed the problem in two ways: one linguistic, one performative. He ironically titled his four week residency “Space Program”, acknowledging the potential for chortling, awestruck consternation when surveying the intimidating enormity of the enterprise, while seemingly looking the devil right in the teeth (like Ahab in Moby Dick) and daring it to swallow him whole. But on the practical side, he also created an extended performance schedule (from May 16 – June 17, viewable at http://www.tomsachsmars.com/) in which he and his crew of a dozen “Space Camp” assistants, each clad in a uniform of khakis, white shirt with plastic pocket protector and skinny tie, like hipster versions of the Ed Harris character in Apollo 13, will simulate the take off, landing and all necessary and imagined tasks of a manned space flight from the Earth to Mars.

The project is co-produced by the Armory and public art powerhouse Creative Time. It is curated by CT’s head honchette Anne Pasternak and the Armory’s consulting artistic director, Kristy Edmunds. And it has been the main thrust, the culmination of Sachs’ art production since his Let’s Go to the Moon installation at Gagosian Gallery in LA in 2007. His five year mission since then: To explore strange new worlds. To seek out new life and new civilizations. To boldly go where no man has gone before.

The fifty-odd sculptural installations dotting the Armory range from a full size L.E.M. (Landing Excursion Module) to a 1972 Winnebago Brave jerry-rigged into a Mobile Quarantine Facility, a golf cart cum Mars Roving Vehicle, an Indoctrination Center, a Repair Station with tools (drills, wrenches) enshrined in plexiglass cabinets, the 40 video screens of the Mission Control Center, various ruddy, polygonal solids (recalling latter day Robert Smithson sculptures) as Martian rocks and craters, several accessorized refrigerators (one with the iconography of Darth Vader) filled with champagne and beer, a hot nuts and tin foil conveyor belt contraption (for the production of in-flight astronaut nutrition packs), and two banks of NASA folding chairs arranged as stadium seating: those on the Park Avenue side denoting Earth; those nearer to Lexington, Mars.

But even more than these material outcroppings, what will resound mightily at the Armory for the next month is the resolute, cult-like devotion and keen purpose of Sach’s mission-to-Mars team of acolytes, who will bike and skateboard around the space in fulfillment of their various Space Program protocols. The public is invited to witness the shenanigans at $10 -15 a visit, depending on event. There is also a gift shop, by now de rigueur in our post Murakami/LVMH art world, where Sachs designed consumer goods can be purchased (more on this later, under branding).

Sachs has established a lot of good will, over the years, for his creation of a skewed reality from the discards of civilization, for his ability to create an alternate universe of objects that closely mirrors our obsessive material milieu and comments on the excessive, late capitalist appetite for sex, violence, entertainment, luxury and leisure. He has impressed us as an enlightened “bricoleur” — a word used in the CT/Armory press release, and since magnified by its inclusion in a score of recent journalistic puff pieces — walking in the funky, beatnik assemblage footsteps of Edward Kienholz, with a soupçon of Jean Tinguely’s post-Dada, kinetic art machine tinkerings, plus the added metaphysical gravitas and urgency of Robert Rauschenberg’s combines.

But for some, Sachs’ shining moment, his penchant for taking it to the limit, for going above and beyond the call of duty to reach new creative heights, was his 1999 installation of homemade machine guns at Mary Boone Gallery, accessorized with a glass bowl of live ammo which attendees were able to take away, resulting in the arrest and overnight incarceration of the formidable Ms. Boone by the NYPD. Watching your dealer being led away in handcuffs should be the ultimate goal of any true rebel artist.

Should a similar fate befall any of the minions of CT, the Armory, or the attendant PR firm Resnikow Schroeder, should one of them get hauled into the pokey by the local constabulary — photos very much appreciated, thank you — allow me to personally congratulate, in advance, each potential perpetrator for their overriding commitment to the Space Program, come what may.

Sachs’ main sculptural material is 3/4 inch plywood, sawed, cut and screwed together, and typically whitewashed with an overall flat, matte finish (signifying “laboratory”) into low rent simulacra of icons that we easily recognize and tend to fetishize: machine guns, ghetto blaster radios, power tools, happy meals from fast food outlets, ready-made tool kits under cellophane wrapping, cameras, giant-sized Hello Kitty statues, chain saws with Gucci or Chanel logos, liquor cabinets/entertainment centers teleported in from the cool jazz, Playboy Magazine, swinging bachelor pad heyday of the 1960s.

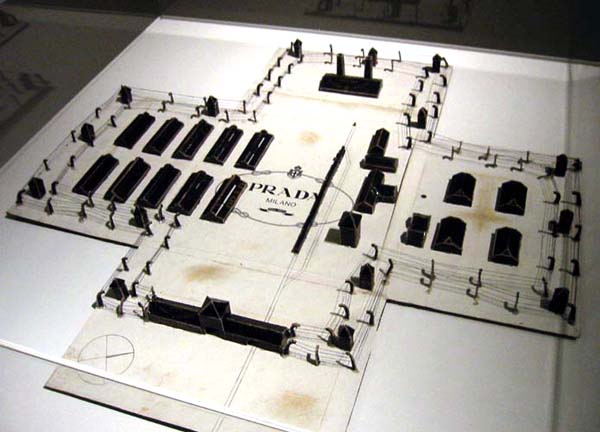

And let us not forget Prada Deathcamp, a reconstruction of Auschwitz fashioned from one of the Italian designer’s hatboxes, which scandalized viewers at the Jewish Museum in 2002. With this assemblage, Sachs confronted the idea of fascinating Fascism, and the ways in which fashion, convention, desire and marketing can oppress us. He maintains a complicated deadpan delivery which challenges the devotional touchstones of our civilization, even something as unapproachable as the Holocaust, with a fierce, arch, gallows humor.

Sachs maintains a studied ambivalence, a gamesmanship derived from the glut of received mass cultural sources such as television, magazines, advertising, fast food, fast cars and (now) the Internet, semi-digested into his stark white effigies and regurgitated back for our consideration. But there is also a certain tenderness, a nostalgia, a love/hate dichotomy which the 45-year-old Sachs brings to his objects. They are, after all, the collective fabric of our lives. They can neither be wholly rejected nor wholly celebrated. They are ambiguous, absurdist emblems.

Which brings us to the issue of branding. It is pervasive in corporate and institutional usage, so by labeling his work with well known identifying logos, Sachs is ruefully acknowledging a worldwide network of ready-mades. The NASA patch and the Nike swoosh even share a common iconography.

Placing the logos of luxury goods on his “generic”, white-on-white constructions has been Sachs’ sarcastic way of dealing with the anxiety of consumption, of distancing himself (and us) from the exalted commodity status of the art work, which is mirrored in the luxury goods commerce of high end clothing, perfume and furnishings. He is obviously both attracted and repelled by the preciousness of the consumer object. But in the current exhibition, Sachs has come full circle, succumbing to the blandishments of commercial production and partnering with the athletic wear conglomerate to produce a line of limited edition NIKEcraft merchandise that includes shoes, jackets, t-shirts and bags.

A last point: there is a studied, matte, white-on-white look to much of Sachs’ artistic production. Taken together with his high tech lighting and other fresh references, it is in direct contrast to the generally somber, 19th Century, Victorian Age shadings of the Armory. Particularly in the period rooms, with their dark cabinetry and wood paneling, these archaic conventions of decor, even of Frankenstein era laboratory furnishings, serve to accent the appearance of Sachs’ sculptures, placing their contemporary appearance in high relief. This dichotomy of decor allows us to consider the possible Steampunk antecedents of Sachs’ work, with their shared DIY aesthetic and ambivalence towards authority. The issue is worth greater consideration in another text.

Since it became a nonprofit cultural space and began to host art installations in 2006, the Park Avenue Armory has been no stranger to the spectacle of weird science masquerading as art, or art masquerading as weird science. With Tom Sachs and his Space Program: Mars exhibition, it seems to be getting a bit of both. May the Force be with them.