Dazzled, then puzzled. An absolutely captivating, visually and cerebrally stimulating, frequently quite hilarious few hours at the Tacita Dean show at the Norton–including a good hour chatting with the artist–and for weeks afterward, trying to re-capture the moment, I’m grasping at air, coming up empty-handed, mind blank: What was that all about?

The unsettling afterglow lingers and then finally, jells–the problem is the solution. The elusiveness is the point. Or a point at least, and a major one: a Cheshire Cat, the mischievous Dean makes many points–about history, about nostalgia and about the process of representation.

Best known for her work in non-narrative cinema, and often grouped among the Young British Artists of the ’90s (a tag she shies from), Dean’s Norton show is the first to focus primarily on her work with photography. But while photography originated as a method of documentation, an effort to capture reality, Dean conjures visions that never were or are almost, but not quite there.

Twenty digitally enlarged images drawn from Dean’s collection of “disaster postcards”–collected on her quests through flea markets around the world–make up The Russian Ending, a project inspired by the early Danish film industry’s practice of making two endings for every film’s market, upbeat for the American and tragic, if not calamitous for the Russian.

Dean’s gallery of grotesques depicts battlefields, shipwrecks, burials (of clergy, often enough), the “dark, satanic mills” of an early industrial landscape–a storyboard or storyboards for what could be the ultimate catastrophe blockbuster. But striking as the images are, the mournful potential repeatedly serves as a banana peel to viewer expectation. Dean fools with history, littering the prints’ surfaces with handwritten “stage directions” that put the dead in deadpan, undercutting the horror.

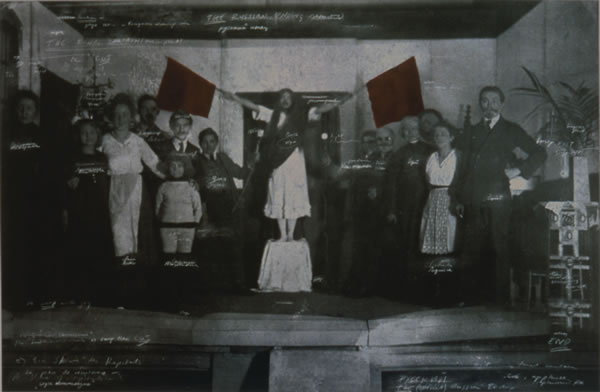

The suite is in vintage black and white, with one exception, an early Soviet gathering, with “Olga” a/k/a “communism personified,” on a pedestal stage center, red flags held aloft in either arm. The group photo includes the instruction “EXIT stage left ->” though of course, the Reds would go “left.” In another photo a corpse is given the direction “no breathing,” in another, a corpse about to cross the River Styx is told “bye-bye.” Above a beached, decaying whale Dean comments “not MOBY DICK/a cheaper production”; of one dead priest she notes “exit (Heaven?)->.” Death and destruction aside, as in the melodramatic redundancy of an upward pointing arrow in the center of a towering explosion, there’s a very sly humor here.

Dean pivots from the grand sweep of history to an intensely intimate moment in Czech Photos, an installation drenched in Eastern Bloc pathos. A collection of 326 snapshots sits in a simple wooden filing box–worn but finely-crafted, with dovetail joints–on an equally worn, schoolroom-size table with matching chair, a wordless invitation to sit and riffle. Seemingly haphazard, the photos show street scenes, countryside, interiors–everyday life after the Iron Curtain is raised–pedestrians in transit, signs and architectural features, some at strange angles. The display is altogether casual in effect, with a suggestion of disposability. With no gloves provided with which to handle the photos, no distance exists between the viewer and the art object. This is a process piece, a paradoxical one, comforting even as it argues–insists–that decay is inevitable in art and, as in life, the price of admission.

Cinematics are at play in some work: the pulsating optics of 142 found postcards in Washington Cathedral, presented in twinned arrays of near-identical images of the building in varied hues and lighting, like a deconstructed film strip; the serendipitous Film Stills, a Pop/Dada set of 14 lithographs of collaged imagery, a sort of vest pocket version of a mammoth set of Dean lithographs previously shown at the Tate Modern.

Other pieces speak to vanishing points, disappearances and falsification.

Trying to Find the Spiral Jetty: Robert Smithson consists of a single 35 millimeter color slide projection, a relic of Dean’s failed 1997 effort to visit the late earthwork artist’s iconic masterpiece, a work which appears only irregularly, as the water level of Great Salt Lake rises and falls. Dean’s photo records a negative epiphany, a blazing ovoid flash of white light where sky meets water, an egg-shaped instant simultaneously void and (literally) illuminated. The suggestion of transcendence is nicely balanced–brought down to earth, as it were–by a droll pairing with Dean’s copy of a facsimile print on paper, Instructions for Trying to Find Robert Smithson’s “Spiral Jetty,” Faxed to the Artist in June 1997.

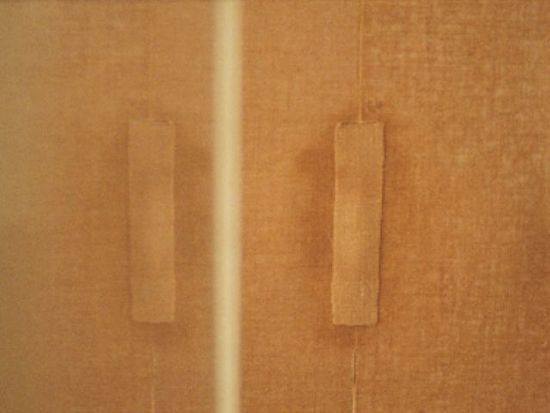

Darmstädter Werkblock is a set of eight color prints, each approximately 2′ x 3′, documenting the walls of a renowned Joseph Beuys installation. The piece is Dean’s response to the controversial handling of Beuys’s work by the Darmstädt museum’s curators, who removed the original jute covering from the installation’s walls and replaced the patched and ragged surfaces with conventionally austere white paint. Dean’s sympathy for detritus and the ravages of time reflects a similar strain in Beuys’s oeuvre, the odd markings evoking the shamanic German’s spectral presence, as though his spirit inhabits the vacant space his work once covered.

Dean’s falsification? Other than to say that it’s a piece consisting of a single image, another postcard-based work, with a clearly defined reference to cinema history, I’m not talkin’. Why spoil the fun? Ms. Dean’s title for the work is a blatant lie, unashamed and gleeful, and I leave it to the canny visitor–or a helpful Norton guide–to reveal.

“Photography is truth. The cinema is truth at 24 frames per second,” Godard famously said. Maybe. But for Tacita Dean, even a lie can be art, and a source of greater truth.

Through May 6

Norton Museum of Art

West Palm Beach