By Steven Scorpio

As if drowning, the history of Western art flashes across the canvasses of Jenny Saville: the pale musculatures of Michelangelo, the agonies of Goya, De Kooning’s bravado, the discomforting torsos of Lucian Freud. These masters are all male, of course, and Saville is steeped in feminist theory. It informs her work thoroughly without in the least limiting it, though since women’s fates–by definition and the hard facts of history–have been bound to the flesh, it is flesh first and foremost that Saville depicts.

A slighter younger compatriot of the Young British Artists of the early ’90s, Saville came to popular attention in the U.S. when her work was included in the controversial 1997 “Sensation” show at the Brooklyn Museum of Art, which provoked the ire of conservative political and religious leaders. Saville stood out in that group for her commitment to traditional figurative oil painting. But while her work was, superficially, light-years distant from sharks in formaldehyde or Holy Virgins with elephant dung, Saville clearly shared her colleagues’ resolutely confrontational approach.

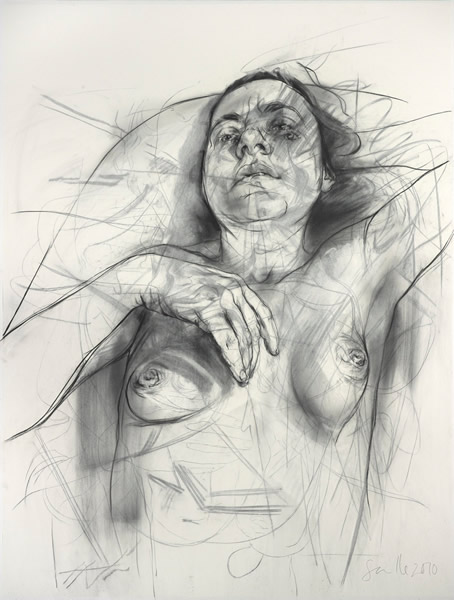

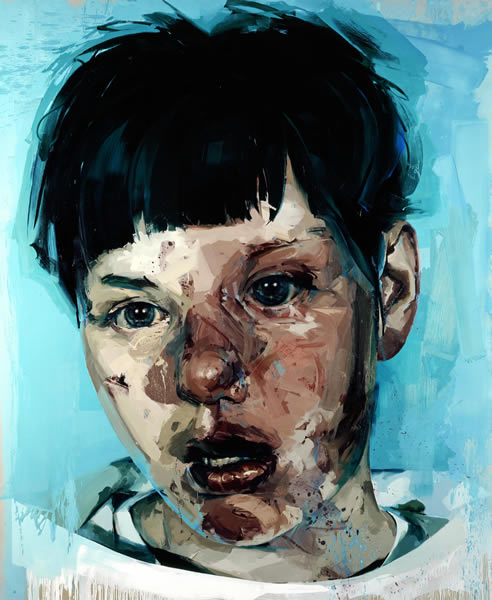

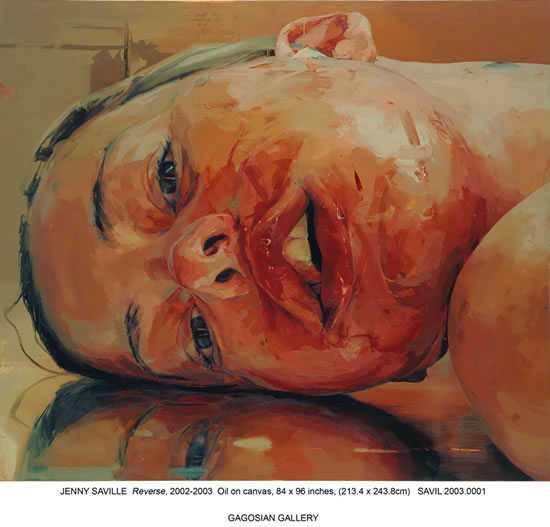

It is no surprise to learn Saville has spent many hours sketching in a slaughterhouse or observing plastic surgeries (where she was intrigued, she says, by the idea of “fictional normality”). Images of pain and disfigurement, restraint and submission, awkward postures fill her canvases. Madonna-like figures speak of angst, not beatitude. Whole heads at odd angles, or bodies stacked like prisoners at Abu Ghraib take up the frame (large scale paintings for the most part–another claim staked on a traditionally male prerogative–six feet and more in width, some as much as ten feet high). Oddly cartoonish suggestions of geometric forms float about. A line of red skitters off a jaw like a tracer bullet in the dark. Except for the occasional shading and suggestions of depth of field, space is left indeterminate, with subjects adrift in physical and psychological space.

And yet there is pleasure, sumptuously. Beauty emerges in isolated features or in the rapture of the pose; the delicate composition of uncomfortable imagery and the careful balance of awkward forms generate delicious tensions. Whether sighted or blind, eyes rich in liquid emotion stare out from wounded faces. The layering of the work is playful and provocative, images doubled and tripled as the first sketches of figures are left in place so that fossils of the artist’s process infuse the canvas with time, cinematically (though Saville says she works toward “narrative within the paint, within the body, outside time”). Most generously, the surface of the body becomes a field of voluptuous abstraction, filled with the sheer pleasure of paint and mark-making in the Abstract Expressionist style.

Saville told an audience at the Norton her chief goal is “to make painting relevant, vital in the face of the screen.” It was unclear to me if she was referring to “the screen” of life, where we are now so bombarded with information, or of the computer, where so much of our experience is now mediated. In a time when the two screens have nearly blurred to one, Saville offers a more primary vision.

Jenny Saville

Norton Museum of Art

Nov. 30, 2011 – March 4, 2012

www.norton.org