“The Wilderness,” Miami Art Museum says, “is an examination of the conceptual boundaries between nature and human civilization. It considers the wilderness not as a place, but as an idea lodged deeply within human cultural history…” The exhibition, including works by David Brooks, Allan McCollum, Christy Gast, Aramis Gutierrez, and Tacita Dean, explores “tamed versus untamed nature” in a selection of installations and presents competing definitions of the wilderness.

The artists of this exhibition, naturally all approach their art practice in different manifestations, but the most exciting projects for me may have been the most “boring” of the exhibition. Of course, boring is not my descriptive word, but I’m absolutely sure someone would say that. It’s used all too often. Anyone who doesn’t find the possibilities open, potentially exciting, and enriching, when art and science merge are who is really boring.

I am especially referring to Allan McCollum in this instance. His project, “The Event: Petrified Lightning from Central Florida (With Supplemental Didactics),” the result of a three-year project sponsored by the University of South Florida and undertaken with the help of a geologist and an electrical engineer from Florida University’s International Lightning Research Facility at Camp Blanding was not a painting or “typical” sculpture but a fulgurite, a tubular specimen of petrified lightning.

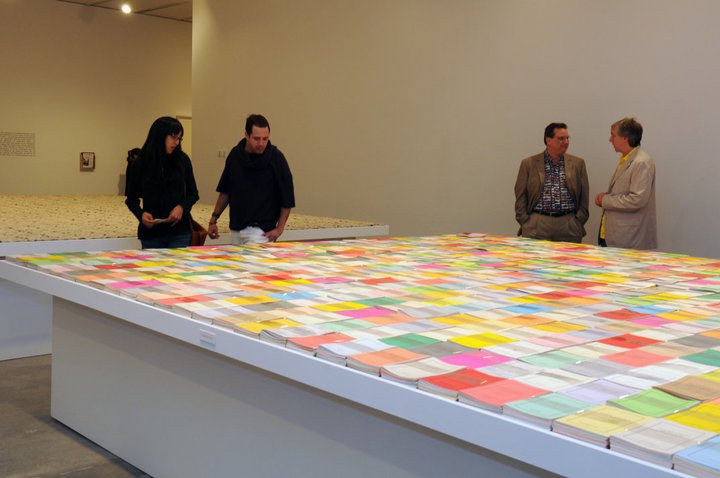

McCollum made his “assisted” fulgurites by firing rockets into thunderheads, triggering lightning bolts directed into a special barrel—in effect, forcing lightning to strike in the same place repeatedly. He then chose a single specimen and had it mass-produced by a Florida souvenir manufacturer. The result was then laid out on tables displaying some of the 10,000 copies of the eight-inch-long object, made of epoxy and zircon sand.

Allan McCollum

“The Event: Petrified Lightning from Central Florida (With Supplemental Didactics)”

eight-inch-long object, made of epoxy and zircon sand

dimensions variable

Photo: Yesikka Vivancos

Of the “Supplemental Didactics”: sixty-six paper booklets, identically bound in drab tan, the words “lightning” and “fulgurite” predominated in the titles. The booklets look like little guide books with texts that sounded technical, while others were drawn from the writings of Kandinsky and Darwin.

McCollum’s art practice has focused on how an art object encapsulates meaning, and what is unique, and what is a copy. However, if one decides to investigate further into the sites he uses, one would find a rich territory of culture, science, and the art making process.

Photo credit: Juan Cabrera

Sometimes artists have to opportunity to do some of the most odd, yet beautiful (intellectually) stuff.

Take the next case. I walk into the gallery area, see all these animals, dark forms of a strange kind of taken apart circus, or zoo, or not, splattered with a milky white and creamy color of paint. No, wait. There are no brushstrokes, and the pourings looked a bit too haphazard. Is it paint; or, what is it that has created the various splotches, drips, and nuanced streaks? Guano? Really!?

“David Brooks is a sculptor and installation artist whose work investigates how cultural concerns cannot be divorced from the natural world. His work is engaged with examining the cause and effect of ecological crisis and questioning the terms under which nature is perceived and utilized.”

“Well!,” talking to myself, “There’s another artist using bird shit (besides myself), and he gets an exhibition.” There is surprise, and hope in my mind that Miami is not as closed minded as I had thought for so long (although my work with guano was in 1999, and maybe Miami wasn’t ready then).

Guano (from the Quechua ‘wanu’, (dung) via Spanish) is the excrement (feces and urine) of seabirds, cave dwelling insectivorous bats, and seals. Guano manure is an effective fertilizer due to its high levels of phosphorus and nitrogen and also its lack of odor. It was an important source of nitrates for gunpowder. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guano)

Back to David Brooks however… he created a new, site-specific commission for the exhibition titled, “Still Life with Stampede and Wild Seabirds.” Brooks spent time in Miami for the de la Cruz Collection’s artist-in-residence program in 2010. His project featured the aforementioned animals (not the strange zoo I thought I had seen, but the type of concrete animal sculptures that adorn many South Florida lawns) juxtaposed with the real wildlife (pelicans and gulls) that struggles daily to survive amid and at the edges of the local urban environment. The guano was “naturally” applied while the sculptures were left to weather and receive their coating of phosphorus and nitrogen.

David Brooks

“Still Life With Stampede”

Concrete and varnish

Dimensions variable

Photo: Yesikka Vivancos

These are the types of works that excite me. Some recognize the natural affinity I have for such art practices that push into investigations of areas normally outside the provenance of the art world.

Special thanks to the Florida Keys Wild Bird Center, the de la Cruz Collection and CasaLin.

(I would like to apologize for not getting this article posted earlier, but as I do not have permission to photograph art works as I see fit, I must wait for venues to provide me with my requests, and there was a mix up in this instance. Thank you for understanding.)

The Wilderness

March 27 – June 26, 2011

MAM

101 West Flagler Street, Miami, Florida

(in the Philip Johnson-designed Miami-Dade Cultural Center)