Among the Nigerian artists I have high respect for, Dr. Bruce Onobrakpeya is one with a very long resume of exhibitions. I would love to curate an exhibition of contemporary art of the African diaspora, focusing primarily on those born on the continent (even though they may live primarily in Europe or the US). That will be on my agenda later this year.

Dr. Bruce Onobrakpeya: My art is linked to the spiritual

From YINKA FABOWALE, Ibadan

Sunday, April 03, 2011

His house, which doubles as his studio and galary, is ensconced in the thick, dancing commune of Papa Ajao in Mushin, Lagos. To get there could be a little tedious, if not torturous – you must fight your way through the chaos and often-capricious Ladipo spare parts market. The two-storey building is not difficult to find once you have been well briefed and directed. One would think that access into the house of a man of Dr. Bruce Onobrakpeya’s standing would be laborious.

It isn’t. You only need to tell the guard at the gate that you want to see Baba and you are right into the premises and into the house. And inside the house proper, you are shown into an art shrine. It is built for that purpose, you’d be told when the patron of this pantheon sits and discusses with you about this universe suffused with marvels in visual art.

While you are lost in this suffusion, he walks in quietly and greets you with a low, shrieking voice. He is unmistakable, not with his gray hair that looks as though it has always been there – and then his welcoming smile. He takes your hand, not very firmly but respectably and friendly. He pulls a chair and asks you to sit. He too sits and without further courtesies, you set off on your mission. “We’ve come, as I told you, to talk with you about your art and the personality behind it.” He simply smiles and says “al–r-i-g-h-t!”Dr. Bruce Onobrakpaye is an artist of renown, both within and outside the country. Because of his prodigious artistic vitality and long, vibrant professional presence, it is easy to ascribe to him a pioneering status. Which was exactly what happened in this encounter with him. But he is too modest to jump at what does not belong to him. “I don’t think I should be called a pioneer. One of the pioneers was celebrated some time ago in the person of Ben Enwonwu.” However, this icon has a dominant, patent place in the cult of visual artists.

A master artist and intellectual, Dr. Onobrakpeya was born in 1932 and trained at the Nigerian College of Arts, Science and Technology, Zaria. As a young man, he taught in various secondary schools including St. Gregory’s College in Lagos. Once an art-in-residence at institutions in the USA, Zimbabwe and in Nigeria, he initiated the Harmattan Workshop series. This is a forum for artists, since 1998. A husband, father and “a good Christian,” Dr. Onobrakpeya talked with us as an icon of the art. He talked freely about his art, his muse, his philosophy and the place of the art in human society. He also led us into his private life, after all, the person is the artist and the artist is the person.

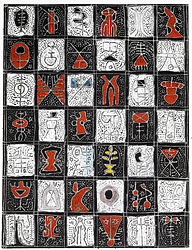

Ibiebe ABC III

Bruce Onobrakpeya born 1932, Nigeria

2000

Additive Plastograph print and ink on paper

H x W: 106.7 x 79.2 cm (42 x 31 3/16 in.)

H x W: 89.6 x 68.8 cm (35 1/4 x 27 1/16 in.) (image size)Museum purchaseThe Ibiebe series by Bruce Onobrakpeya features his invented script of ideographic geometric and curvilinear glyphs. The designs reflect the artist’s knowledge of his Urhobo heritage, rich in symbols and the proverbs they elicit, as well as his appreciation of Chinese and Japanese calligraphy. Onobrakpeya invented and refined this script from 1978 to 1986, when he revisited in his art ideas linked with traditional religion, customs and history. The artist clearly delights in the script’s forms and visual qualities as well as its power to communicate.Excerpts:

Is it right to say that you are one of the pioneers of Nigeria’s visual art?

In don’t think I should be called a pioneer. The pioneers, one of them was celebrated some time ago in the person of Ben Enwonwu by way of a book written on him by Sylvester Ogbechie. He was a pioneer and before him was Inan Abobu. As colleagues and contemporary to Ben Enweowu you have Lashikan and Akeredolu.Those are the three or four principal pioneers that we can actually name in the country. My colleagues and I are the second generation artists and whether we like it or not, our inspiration would come from those I have just mentioned. Although since independence we have made some waves and that’s understandable because we are many – myself, Damas Nwoko, Uche Okeke, Yusuf Grillo, Odita, Nduka Osadebe and so on; seven original members of the Zaria Arts Society, although there were several associate members later. Simon Okeke died during the civil war, Nwagbara also died, but the rest of us Zaria Arts Society are alive and working. We were able to gather momentum that was absent among those earlier pioneers. That’s the difference. I concede Nigerian pioneer positions to those people I first mentioned.

Your generation and that of Enwonwu’s are a neat watershed and critics and writers make serious reference to your idioms, your school and your time. How indeed, has art come over the years?

It’s been a big struggle. If you are an artist and you are doing something, don’t just rest on your oars; that one is talented or attended a very good school, arts is very consuming, and you have to do it relentlessly, take it as seriously as people take other professions, as it is in other profession like architecture, medicine etc.If you really want to get meaning in it, you have to practice. In our own case, we experiment. Show your work and try to be relevant to the society and you try to also show the people around you that art is something that heightens life; it makes you grow bigger. Once all these elements are correct, then the people will always relate to you as someone in a profession that is contributing to the life and the well-being of the society.

Today, where is the place of African art in world art?

African art has one very important significant position, though there are other lesser ones too. That position is that over the Millennium, it contributed to the life of the people vis-à-vis their religion, their philosophies, their sorrows their joys, life expectations, they are all encapsulated; that’s one. Two, African art, at the turn of the century, influenced world art. What is being referred to today as modern classical art, actually originated from African art. People like Picasso and Brachs and a few other people in Europe got tired of producing naturalistic art and so on.They craved change and that only came by their drawing inspiration from African art, which was years ahead of its time. African art look at the spirit of the idea, not the physical essence of the idea. Consequently, African art gave a rebirth to European art. In a nutshell, African art was very useful to the lives, the religion, and the philosophies of the people. African art also gave birth to a new art form in Europe. Those are two broad importance of African art.

Is it right to say that post-modernism Picasso is basically African; that Cubism derives from African art form?

We have reached a stage whereby our forms are geometry; they took to African art form and spirit to get out of the old European cliché.

Recently, if the outside world wants to make reference to African art, it is often Southern African motifs. So, where is the Nigerian art in the African art?

The arts of Africa that were known to the rest of the world were Nigerian arts and German traveler Leo Phobillus first discovered that. He traveled round the world and took Nigerian arts to Europe; the second big wave that took African arts to Europe and the rest of the world was the Benin massacre of 1897, when Benin art was looted and sold to many collectors all over the world, that brought Nigerian art and by extension African art to the limelight. Unfortunately, it took many years for European experts to acknowledge that these arts that were taken as war booty were really very high arts. Today it is known that the first artwork really to get to Europe to show African art, as art that is worth collecting was the Benin art collected in 1897.

There was a burst of art activities in the 1990s, now it seems there is some quiet. Is this a affair assessment of the art scene?

The wave of independence produced many artists not only in the visual arts but also in literary; that was the age that produced Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka, Amos Tutuola and a host of others. There was a ferment around the independence and art started as a movement, but then there has been generational shifts. Sometimes, it’s a bit quiet, in another time it is high. Following the kind of devaluation that came about the time of (Gen. Ibrahim) Babangida; before that, visual art was in high tempo, but after the devaluation and the subsequent political crises and so on, art went down. But I want to tell you that right now, art is going up.Last year was very vibrant in the production of the art; many exhibitions, many auctions and a new kind of feeling emerged in the art scene, which of course, all the time makes the art go up. It was this time last year that we had auctions that brought into the limelight a few practitioners of mixed age and generations and that is continuing. I would not say that art was upbeat only around the independence era; right now it is even on the upswing.

The other time, there was an auction of works of the masters, including some of yours; there your works raked in millions of naira and that was unprecedented in the history of art in this country.How did you feel?

It was at the auction put up by Cavita Chellarams, the one that made the big wave. Grillo, Osunde, Oshinowo, Abayomi, others and myself. What was spectacular, what brought the high price was the exhibition of contemporary arts auctioned by Cavita Chellrams. The director was Cavita Chellarams and that was what brought the super price by Nigerian standard. That was something we have all been looking forward to; we have been working all these years; sometimes it becomes a routine to work hard, whether your work is admired or not. If I had known that there was going to be so much light at the end of the tunnel, one would probably have worked harder; that was the feeling, but it was satisfactory because for many years, if you are observing what is going on, the artist has been pushed back.Right from when we were in school, the prevailing sentiment was that we went into the arts because we were unable to excel in other fields such as mathematic or the sciences. But when that auction happened, most people were forced to rethink and say: “So there’s something there after all” and I know people who went back to their private vaults and dusted some art work collected by their fathers that they never thought anything about.

Artists are now encouraged, they have become important in the eyes of the people and the profession is no more relegated to the background; collectors are now proud of their collections because they know that someday they can recoup their money at even far above the cost price. Collecting arts now becomes akin to collecting gold or investing in premium properties. Arts can now be used as collateral.

It seems that aside Oshogbo, you hardly can distinguish other art schools in Nigeria. Is this healthy for art development in the country?

The Oshogbo group was articulate and voluble and hence the name stuck. They stayed and worked together as a group for sometimes, which makes the name stick. But there are other groups; you know of the Uli School by Uche Okeke. He developed this old Uli arts from the old sign to the contemporary use; and of course those of us from Zaria, they regarded us as the Zaria group.The Zaria group splits into smaller groups; the Uli group is one of them. The followers of Grillo constitute another group; we the fallout of the Harmattan workshop, we are another group. It is just that we did not become one single name like the Oshogbo group, but they are all there as groups. The numerous groups can be traced back to a particular family tree where they evolved. So we have many groups, it’s just that about two or three are better known.

What are your muses, your motivations?

My motivations are life, the environment. I enjoy the thought that there are a lot of things that we have inherited, our legacy, not only arts now but also philosophy, history, religion and so on. These are materials you can draw from.

What do you call your kind of art?

My kind of art is experimental art. I try to fuse many ideas together in order to get something that is new, the old and the new to project the future. My art belongs to the synthesis group which is the name given to the Zaria art society group. The synthesis theory is that you look at the old art and extract the valuable things and add equally valuable ideas from outside; there’s a fertilization, use that to produce arts for now and project for the future.That is the synthesis theory, which the Zaria art society propounded. Apart from that, I believe very strongly that the environment around me has a lot of inspiration through history, folklore, philosophies – they all constitute very rich materials to use to develop and experiment, mix them up, change them a little bit and then move forward into the future.

Most of your themes and motifs are traditional, why are you stuck to the past?

I am not stuck to the past. I get something from the past and upgrade it; extract what is good from it and add some other fresh elements as catalyst, then come up with something totally new. So my art transcends the past to the present and to the future.