Legacy: The Emily Fisher Landau Collection

Whitney Museum of American Art

945 Madison Avenue at 75th Street

February 10–May 1, 2011

February 10, 2011. In a bit of serendipity that is hardly lost on the Whitney Museum itself, the exhibition they just opened, of work from the collection of Emily Fisher Landau, is mounted in fourth floor galleries that already honor her name. The estimable Fisher Landau collection, totaling over 400 works, was pledged to the museum in May 2010 by their longtime trustee, who has also established an endowment for continuing support of the Biennial. The show currently on view, comprising just over 80 pieces, is assembled by Whitney curators Donna De Salvo and David Kiehl, and ranges from signature work by Andy Warhol, Edward Ruscha, Richard Artschwager and John Baldessari to a vintage 1980 Susan Rothenberg new image painting, a wealth of Jasper Johns screenprints, pristine early 60s works on paper by Agnes Martin, Carl Andre concrete poetry on typewritten sheets, Felix Gonzalez-Torres jigsaw puzzles, assemblages by Nayland Blake, photo portraiture by Peter Hujar and Nan Goldin, and an early Richard Prince nurse painting, to name but a few.

It is an embarrassment of riches. As Whitney Director Adam Weinberg indicated in his introductory remarks to the media preview, for a museum to be gifted a collection of this scope and quality is positively overwhelming. Referring to the augmentation of the museum’s holdings made possible by the Fisher Landau gift, he seemed as giddy as a kid let loose in a candy store. I would add that, at a moment when the institution is looking to expand its focus downtown to a new, large Renzo Piano-designed facility at the southern terminus of the High Line, the incorporation of so much world class work in one fell swoop is an expansion of equal and complementary importance.

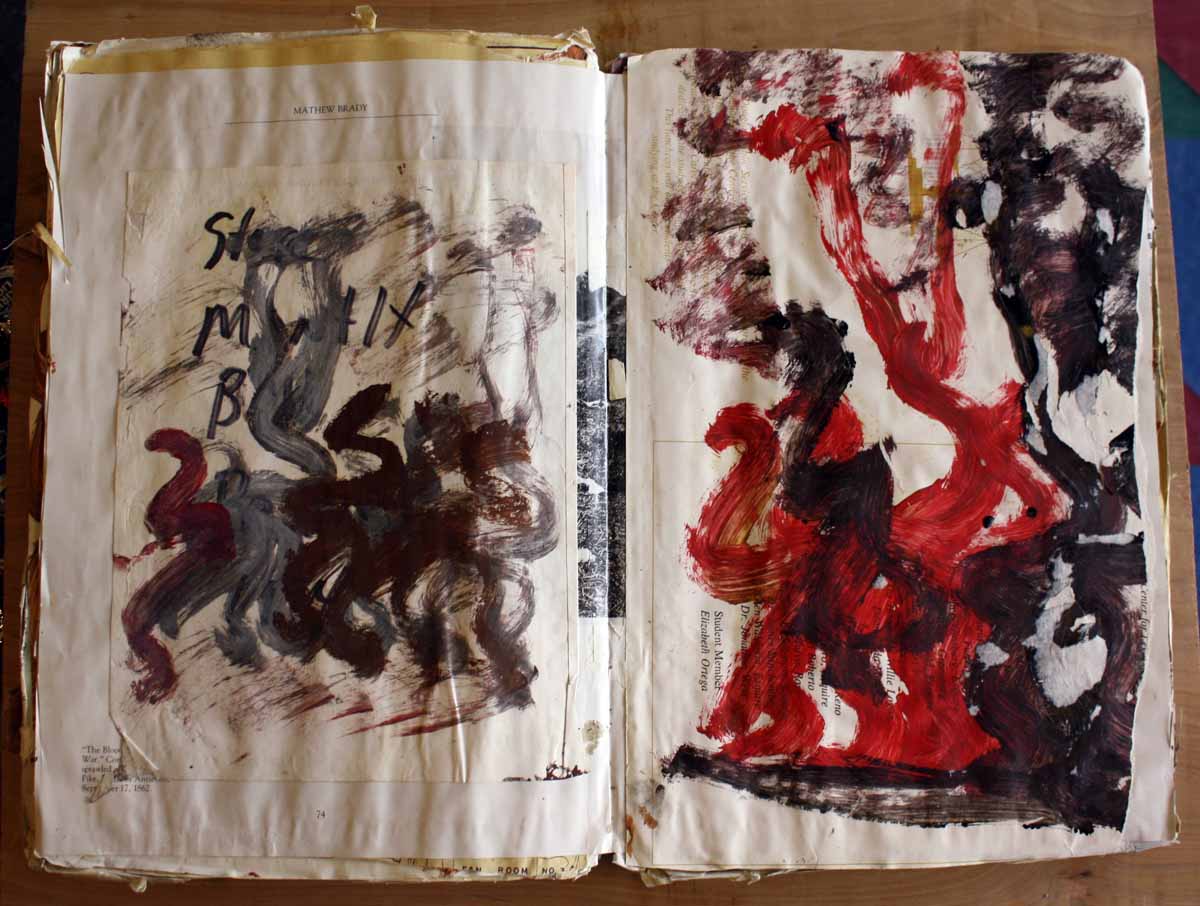

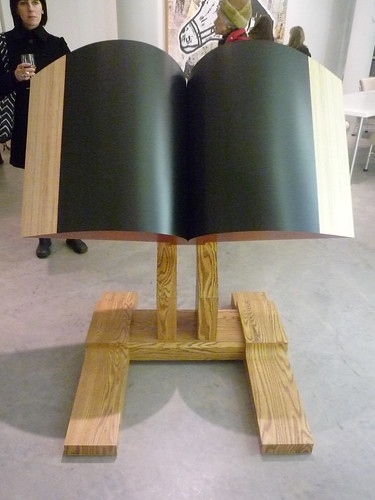

I have never met Fisher Landau nor been to her home, but have attended numerous events at what must be considered her spiritual home, the art center she established in Long Island City, Queens in a former parachute silk factory. It is a large, well proportioned concrete building off the N line. I have visited there often enough to become accustomed to seeing particular pieces in particular places. For example, the Jenny Holzer granite benches on various stairwell landings, the 1984 Warhol portrait of Fisher Landau opposite the information desk in the lobby, the Artschwager lectern/open book piece in the library. To now find these relocated to the Whitney, relegated to a more general and possibly impersonal population, brings a mix of emotions. While the work has undeniably found a new, secure and institutionally viable locus, it also seems excised from its original, natural habitat. This passage from intimacy to institution is marked by the very first piece we encounter off the Whitney’s fourth floor elevator, an 11-foot-wide Ruscha from 1983 with the words “The Act of Letting a Person into Your Home” displayed against one of his patented desert sunsets.

There is, possibly, a sadness that accompanies all notions of progress and growth. To see a collection nourished over the years by Fisher Landau’s impeccable eye, with good advice by her longtime curator Bill Katz, relocate en masse to the Whitney’s hallowed halls brings a certain ambivalence. Something is lost, even while something is gained.

What is certainly gained is a new curatorial imprimatur, a new perspective on cross sectioning the collection, and one of the joys of the current exhibition is when it veers from the central canon of Johns/Warhol/Artschwager/Ruscha – all of whom Fisher Landau collected throughout their careers – to her more quirky, idiosyncratic choices. For example, the 1988 Al Taylor sculpture, a helix composed of painted broomsticks mounted off the wall. The two vintage Neil Jenney text/image paintings from 1969. A 1992 Peter Cain squished car painting. Two classic 1984 works by Carroll Dunham, when the imagery, already polymorphous perverse, had not yet started its full descent down the rabbit hole of sexual orifice. A 1990 Mark Tansey existential conundrum, predating both Schejldahl’s rejection and Gagosian’s adoption. Two excellent David Wojnarowicz collaged map combines (1987, 1990).

The current airing of the Landau collection culminates with two pieces on the fifth floor – a 1958 Georgia O’Keeffe and a James Rosenquist mural – that bring us to another good reason to visit the Whitney: Singular Visions, an exhibition of twelve works drawn from the museum’s permanent collection, each given its separate room. It tweaks the usual cheek-by-jowl assortment of permanent collection trophies into a subdued, pensive, mysterious, installation-driven display that gives some indication of what the Whitney might do with all the extra space it creates for itself downtown. Highlights among Visions include George Segal’s “Walk/Don’t Walk”, Gary Simmons’ boxing ring with tap dance shoes hanging from the ropes and dance step markings chalked onto the black mat, Eva Hesse’s hanging web, and AA Bronson’s chilling deathbed portrait of his General Idea partner Felix Partz.

Also notable: Jonathan Borofsky’s wall drawing wrapped around the stairwell, Edward Kienholz’s funky, musty installation that includes institutional mascot Peetie the parakeet, and Robert Grosvenor’s “Tenerife” (1966), a site specific installation that incorporates controlled access, dynamic angles and bold cantilevering off the ceiling to splinter a knife-like form into morphing shards of perception. It delivers an essential sculptural frisson, and is one of the best reasons to make sure you do not neglect floor 5M in your visit to the museum.