Charles Stainback, curator of photography at the Norton Museum of Art, told the opening night crowd for Now WHAT? that he’d wondered what the museum’s new director, Hope Alswang, would make of the “wacky” proposal he and curator of contemporary art Cheryl Brutvan had dreamed up: The two would mosey on down to Art Basel 2010 and, over the course of several days, put together a show of some of the best new work they found there. The result is a testament to the two curators’ fine eyes and impeccable taste, and to Alswang’s faith in them.

The Norton describes the show’s theme as “information exchange,” which works well, and is timely. I came to see the show through another, perhaps equally wide lens: Obsession.

Tenacity and intelligence undergird the show’s works, each piece seeming to emerge from the scratching of an aesthetic itch rather than the pursuit of a pre-determined image. The formal qualities of the pieces are varied, but they are united by an intense, and labor-intensive, working through of what if’s. There is spontaneity here, but it resides in the small gestures and choices of individual elements of the work–enough to bring warmth and humanity. But by and large, it is termite-like persistence that energizes the show.

Established names like Roxy Paine and Liza Lou are present. Paine’s “Pigeon Holes” is an exercise in taxonomy, conflating science and satire in a large-scale construction of thick skids of polymer catalogued–with one, wry insect–in a mahogany grid under plexiglass. Lou evokes Islamic art with “Offensive/Defensive,” a brilliantly colored, richly detailed patterning of glass beads on aluminum, the unsettling outline of some vaguely human figure drifting across its surface, a ghost of disorder.

Appropriately, however, for a show about “now,” the bulk of the work comes from younger and emerging artists, and much of their art radiates the delighted, excited purity of youthful self-discovery. It is work that lingers in the mind’s eye.

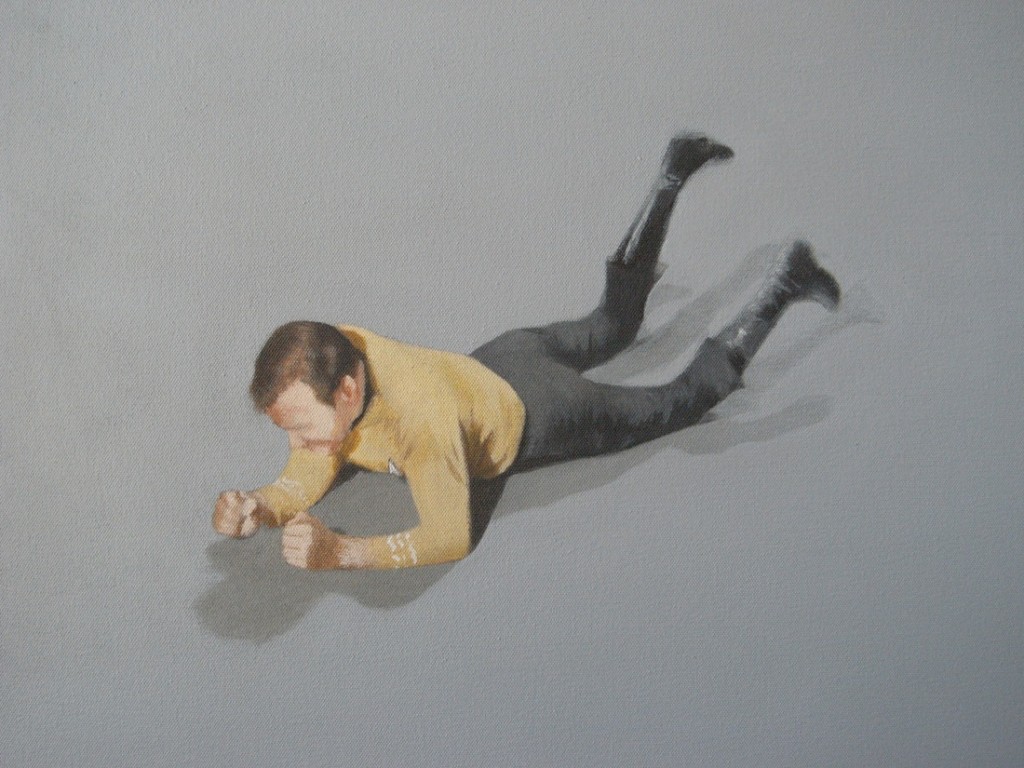

Strangely, and despite myself, I was greatly struck by two acrylics on canvas by Luke Butler, an under-forty, New York-born West Coast artist, both centered on images of actor William Shatner as Star Trek’s Captain Kirk. On backgrounds void of figures or any indication of depth, in washed-out pastels reminiscent of Luc Tuymans’ paintings on world historical topics, these Kirks lie eyes shut and face up, or in tantrums belly-down, as if in stills from scenes of great dramatic import. It could simply be funny, but there is a perplexing pathos in Butler’s fascinated play on the cult-like devotion inspired by this most wooden of actors, a tender concern for so failed a hero.

There is an even more hermetic air to the work of Christopher Russell, another, even younger, West Coast artist. His hand-illustrated, 30-page book “Runaway” and its accompanying wall of 18 mixed-media works on glass, “Runaway: Ghost-Ship-Wreck,” are a fractured narrative of some 19th century maritime disaster. The images, etched into the white-on-black cast of photo negatives, are haunting in every sense, a glimpse into the nightmares lonely children fall prey to in the absence of the light.

Other of the show’s works reflect more tightly focussed techniques, though, like a drill through a tunnel, their singularities issue forth into blossoms of effect.

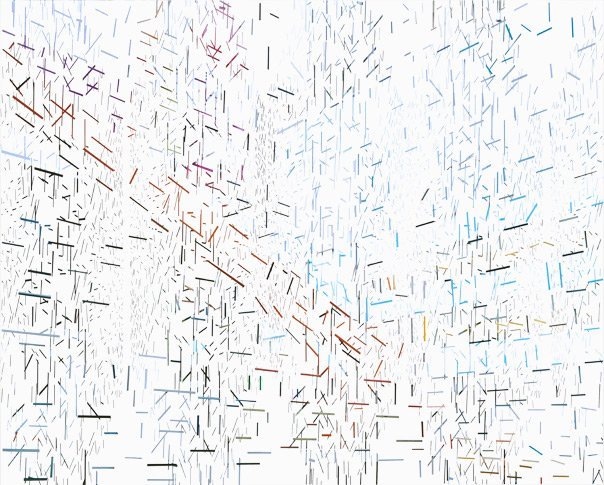

Kim Rugg’s “The Story is One Sign” and Richard Galpin’s “Splinter XVII” have similar strategies, a calculus of subtraction applied to a single, original image. Allyson Strafella’s “foundation” and “inverted red catenary” invert their approach, though her accumulative method also involves disintegration.

Splinter XVII

Peeled photograph

172 x 194 cm 67.77 x 76.44 in

Richard Galpin, 2010

Rugg’s piece takes one page from an issue of the New York Times and reproduces thirty copies of it, every appearance of all but one letter or character blotted out on each page. The instances of the exempted letter or character call out to the viewer like secret constellations or the Morse code of a lost nation.

Galpin’s piece originates in a large-scale photograph of a cityscape, from which he painstakingly peels away strips of emulsion, reducing and altering the visual field to a grid of abstract forms, Constructivist in its geometry, Futurist in its dynamism.

Strafella’s medium is ink and paper, her tool the typewriter, her technique to strike (obsessively) a single key as transfer paper moves through the machine until, through the accumulation of ink and the wear of the paper, forms emerge which are then transferred from the carbon to plain paper. The resulting images have the elegance of miniature rock gardens, the austere saturation of late Rothko.

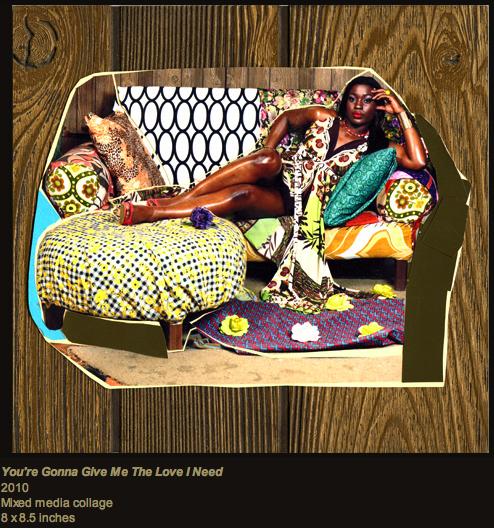

There is more, and among other standout pieces: Brian Drury’s “Ali” is a portrait in oil on wood, the subject’s intensely thoughtful face against a high-gloss red, exactingly detailed in a gripping, almost photorealist way. Seattle artist Isaac Layman’s “Blackout” transforms a large-scale photograph of a window shrouded in a blackout sheet into a hyperrealist meditation on framing. Mickalene Thomas’s “You’re Gonna Give Me All the Love I Need” is a voluptuous, rhinestoned, African American odalisque, the culmination of a process that leads from tableau vivant to photograph to acrylic and enamel on wood.

At a moment when, as critic Peter Schjeldahl recently wrote, art seems to consist of “one damn thing after another” (and when visitors to Art Basel and its satellite fairs can feel drowned in a tsunami of commerce and ego), Now WHAT? offers a distillation of aesthetic clarity, seriousness of purpose and, not least, pure pleasure. If this is the “WHAT” that’s “now,” even the most jaded arts lover can take heart.

Now WHAT?

Norton Museum of Art

Through March 13, 2011

www.norton.org

2 thoughts on “Now WHAT? at the Norton”

Comments are closed.