There is a gem-like little show of work by Vik Muniz, the Brazilian-born artist famous for large-scale photographs of images composed out of non-traditional materials—chocolate, glitter, dust, trash—at Whitebox, the pocket gallery that rests at the heart of Whitespace, the innovative, West Palm Beach exhibition space.

In its cocoon-like setting the show, “A Slice of Time,” invites meditation. The four walls bear just four oversized prints, the end result of the laborious processes Muniz used to transform found or manufactured detritus into one portrait and three re-visions of art historical landmarks. It is nicely balanced against the leisurely ramble of similarly innovative contemporary work from a globe-spanning array of artists that sprawls throughout the warren of walls and walkways in the larger space outside it.

The intimacy of Whitebox and the abundance of Whitespace reflect the personal aesthetic of collectors Elayne and Marvin Mordes, whose home is in residential quarters within the lakefront former commercial building that encloses the art.

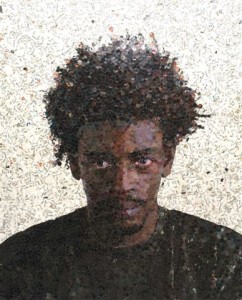

The Muniz prints are in a muted palette. Browns and dark greens dominate the two “garbage” pictures and a portrait ; black, white and grey are all there is to a re-working of an iconic Lewis Hines photograph. All have the easy grace of technically accomplished representational art–a readily digestible formal balance and compelling subject matter. Other critics have noted how accessible Muniz’s work is, and how that has lead many to dismiss it as aesthetically shallow.

The nay-sayers are wrong. The conceptual dimension of Muniz’s work is multi-layered, and its ideas play off and reflect each other like mirrors in an infinity box (and there are pieces in Whitespace that create the same, vertiginous effect with actual mirrors).

“Jorge,” which appears to be a photorealist portrait of musician Seu Jorge, upon closer inspection is composed of hole-punched dots painstakingly arranged so that color and shadow result in the headshot. Like the Chuck Close portraits it resembles, the swarm of detail dissolves with distance into a single, larger image. The single image, in turn, has been photographed and blown up, so that the final product, a 7 ½’ by 6′ Cibachrome print, reflects a process of destruction and accumulation, compression and enlargement.

“Pictures of Paper: Dallas Mill, Huntsville: 1910, After Lewis Hine”

“Pictures of Paper: Dallas Mill, Huntsville: 1910, After Lewis Hine”

There is also a subtle bit of cultural intrigue to the work. As a musician and performer, Seu Jorge enjoys international renown. The dots, reportedly, were punched from the pages of celebrity magazines. Muniz has defaced these depersonalized commodities and used the waste to build a highly personalized face, in tribute. It may not be, first and foremost, a critique of mass media, but the contradictions are suggestive.

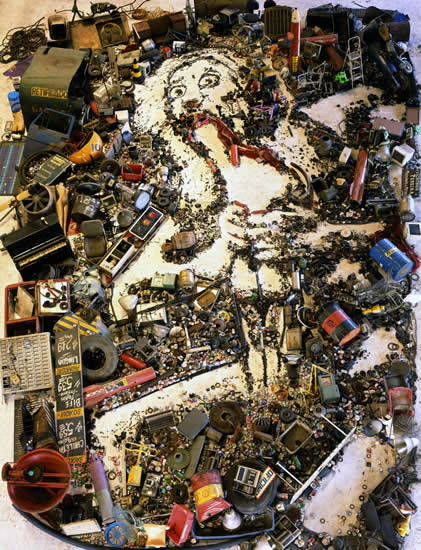

Art history adds a temporal dimension to the three other pieces, and that dimension runs parallel to Muniz’s manipulations of materials.

In “Pictures of Paper: Dallas Mill, Huntsville: 1910, After Lewis Hine,” Muniz has reworked his “Jorge” technique, this time using torn paper in shades of grey, layering it over a copy of Hine’s classic, early 20th century photo (of child laborers outside a factory gate) then photographing the result. The image is a near-exact replica of the original, but with a ghostly caste, a reminder that the original (Hines’ photo) was but an echo of a reality (the mill tableaux), and that what we are looking at is an echo (Muniz’s photo) of an echo (Muniz’s papering) of an echo (Hines’ photo).

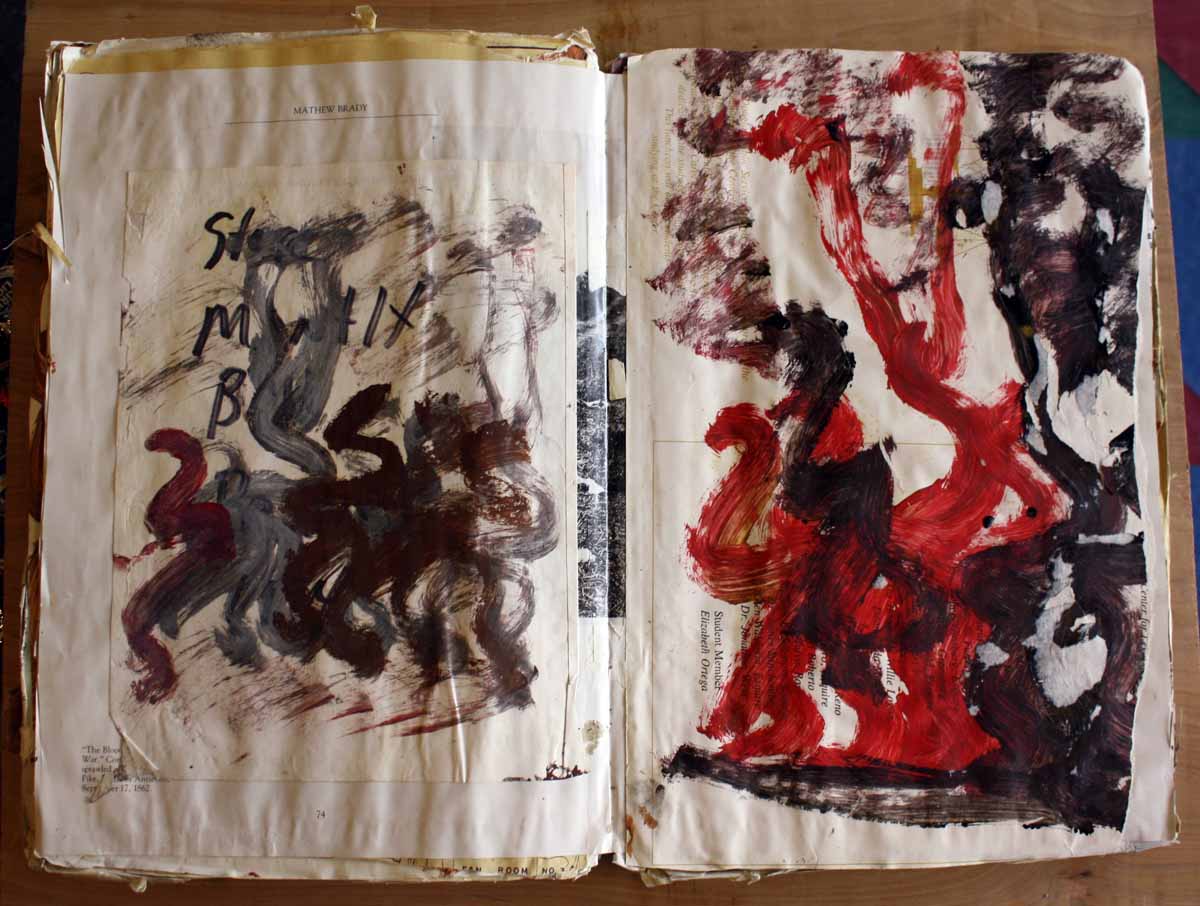

This doubling and distancing reappears in two pieces at Whitespace from Muniz’s “Pictures of Junk” series: “Saturn Devouring One of His Sons, after Francisco de Goya y Lucientes,” and “Medusa, after Caravaggio.”

These are works Muniz has produced with the help of the catadores—garbage pickers—of Jardim Gramacho, a 321-acre open-air dump on the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro. Under his direction, these poorly-paid workers transform what had been trash into assemblages that mimic images from the history of fine art. The completed works–Muniz’s large-scale photos of the images—are a recycling (via photography) of art recycled via recycled materials. They have a comic grandeur, ennobling Brazil’s underclass and suggesting a wry commentary on the malleability of high art.

The Whitespace show is something of a collaborative effort, as some of the Muniz works are on loan from the Margulies Collection, in Miami. The show also includes video, the trailer for “Waste Land,” a documentary about Muniz’s work with the catadores and how that engagement fits into the rest of Muniz’s life and work.

The current show is the first of a Whitebox series that is the key focus of season two of the Mordes’ multi-year plan to make their collection more public, with expanded hours and activities to draw more of an audience. Each opening night includes collateral work by photographer Jacek Gancarz and performance artist Jackie Tufford, two local lights.

“A Slice of Time” will be open to the public on five more occasions between now and January 2. Private tours for visitor groups are also available, arrangements on request. Even with its limited viewing hours—and as the Muniz show demonstrates–Whitespace is already the most au courant contemporary arts space in South Florida outside Miami.