text: Whitney Museum press release

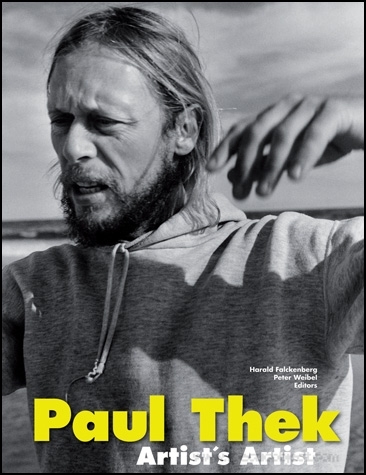

NEW YORK, August 6, 2010. An artist who defies classification, Paul Thek (1933–1988), the sculptor, painter, and creator of radical installations who was hailed for his work in the 1960s and early 70s, then nearly eclipsed within his own short lifetime, is the subject of an upcoming retrospective co-organized by the Whitney Museum of American Art and Carnegie Museum of Art. Paul Thek: Diver, A Retrospective, the first major exhibition in the United States to explore the work of the legendary American artist, debuts in the Whitney’s fourth-floor Emily Fisher Landau Galleries, from October 21, 2010 to January 9, 2011; it travels to Carnegie Museum of Art, from February 5 to May 1, 2011, and then to the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, from May 22 to September 4, 2011.

Co-curators Elisabeth Sussman, curator and Sondra Gilman Curator of Photography at the Whitney, and Lynn Zelevansky, the Henry J. Heinz II Director of Carnegie Museum of Art, write in their catalogue introduction, “If today his art appears more relevant than ever, it may be because so many in the art world have hearkened to Thek’s tune and moved closer to the art he made: an art directly about the body; an art of moods, mysteries, and communal ideas; an art that was ephemeral, disrespectful of the conditions of museums, and that essentially ceased to exist once an exhibition closed.”

The title of the exhibition, “Diver,” refers to paintings that Thek made in 1969–70 on the island of Ponza, off the coast of southern Italy, possibly inspired by the cover slab from the Tomb of the Diver, an ancient fresco unearthed in Paestum in 1968. It is also a metaphor for the artist’s plunge into the unknown and the ongoing pursuit of meaning that is present in all of Thek’s art.

Thek came to recognition showing his sculpture in New York galleries in the 1960s. The first works he exhibited, made beginning in 1964 and called “meat pieces,” resembled glistening pieces of raw flesh housed in geometric Plexiglas boxes. After creating The Tomb in New York in the late sixties—an astonishing installation that was an effigy of the artist laid to rest in a pink ziggurat—Thek left for Europe, where he built extraordinary environments, drawing on religious processions, the theater as tableau, and the common experiences of everyday life, and often employing fragile and ephemeral substances, including wax, latex, sand, and tissues. He also worked in Paris with theater director Robert Wilson (who now administers Thek’s estate) and held exhibitions of his small sculptures and paintings on newspaper at galleries in Cologne and Paris.

After almost a decade in Europe, where he achieved a considerable degree of fame, Thek changed direction, moved back to New York, and turned to the making of small, sketch-like paintings, although he continued to create environments in key international exhibitions. He never achieved the same notice in the US as he did in Europe. With his frequent use of highly perishable materials and his pull toward performance, Thek accepted the ephemeral nature of his art works – and was aware, as writer Gary Indiana has noted, of “a sense of our own transience and that of everything around us.”

Thek died in 1988, at the age of 54, from complications from AIDS. Since his death, Thek, who fascinated fellow artists during his lifetime, has been rediscovered by younger artists. Interest in his work has been strongest abroad and has resulted in surveys in Holland, and most recently, a three-city traveling exhibition in Europe. Until now his work has not been assembled for a retrospective in the United States.

Lenders from many private collections and institutions in Europe and the United States are making work available. Many of the approximately 130 objects in the exhibition have not been seen in the United States in the decades since they were made; others have never been seen here at all. An exceptional number of Thek’s “meat pieces” or Technological Reliquaries, made of beeswax, painted with fluorescent paints, and enclosed in Plexiglas boxes, will be shown. (These anticipate more recent art by Damien Hirst and Robert Gober, among others.) The exhibition includes such rare works as Untitled (Dwarf Parade Table), never before seen in this country, and Fishman in Excelsis, a latex cast of Thek’s naked body with multiple casts of fish clinging to it, bound to the underside of a table and suspended from the ceiling; the latter is from the collection of the Kolumba Museum in Cologne. Other important elements that were part of Thek’s now-lost European environments will also be shown here for the first time. With respect for Thek’s own installation aesthetic and his acceptance of the ephemeral nature of his work, the curators are not attempting to reconstruct environments or exhibitions from Thek’s lifetime. In addition to key elements, vintage photographs and a film will be on view. Another key feature, never shown so extensively, are the artist’s journals, lent by Robert Wilson’s Byrd Hoffman Watermill Foundation.

About the Artist

Born in Brooklyn in 1933 and raised in Floral Park, New York, Paul Thek—whose birth name was George Joseph Thek—moved to New York City in 1951, where he attended the Art Students’ League, Pratt Institute, and Cooper Union. Among his friends and fellow students were photographer Peter Hujar and painter Joe Raffaele (later Joseph Raffael). While living in the East Village, Thek worked as a clerk at the New York Public Library a waiter, and a lifeguard. After school, he moved back and forth between Miami and the Northeast, painting, designing sets, and supporting himself with various odd jobs. (Thek’s nomadic existence later included periods living in Amsterdam, Paris, and Rome, in addition to New York, where he always kept his studio on East 3rd Street. He frequently retreated to the secluded island of Ponza, off Italy, and to Oakleyville, a remote section of Fire Island.) After returning to New York in 1959, his circle included, in addition to Hujar and Raffaele, the artists Eva Hesse and Ann Wilson, the critic Gene Swenson, and the writer Susan Sontag, who became his great friend. Sontag later dedicated to Thek the American edition of her landmark book of essays Against Interpretation (1966).

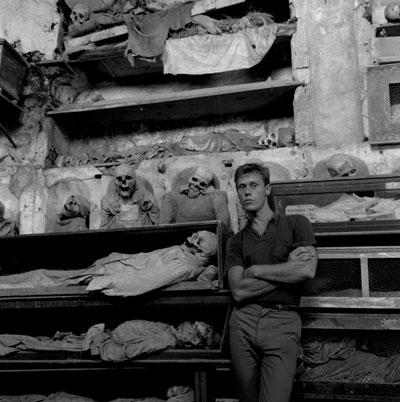

The relationship between Thek and Hujar developed into one of the most important in both their lives. They spent the summer of 1963 in Sicily and visited the Capuchin catacombs near Palermo, where Hujar took unforgettable photographs, and where the rows of human remains in glass boxes had a profound impact on Thek’s work. In Rome, Thek made his sculpture La Corazza di Michelangelo, covering a plaster miniature breast plate in paint and wax. This is the oldest piece in the Diver exhibition. Shortly after his time in Rome, Thek began making his Technological Reliquaries, or “meat pieces.” He showed these at his first New York exhibition, in 1964, at the legendary Stable Gallery. Placed within Plexiglas boxes and hung on walls, the works were deeply disturbing and were taken by many as a comment on the cool remoteness of the geometric sculpture then on view in New York galleries (work later called Minimalism).

In an interview with Gene Swenson in Artnews (April 1966), Thek commented, “The dissonance of the two surfaces, glass and wax, pleases me: one is clear and shiny and hard, the other is soft and slimy…At first the physical vulnerability of the wax necessitated the cases; now the cases have grown to need the wax. The cases are calm; their precision is like numbers, reasonable.” In a 1969 interview with critic Emmy Huf in the Dutch paper De Volkskrant he said: “In New York at that time there was such an enormous tendency toward the minimal, the non-emotional, the anti-emotional even, that I wanted to say something again about emotion, about the ugly side of things. I wanted to return the raw human fleshy characteristics to the art.”

In 1966, Thek began making casts of his own arms, legs, and face. The sculptures that resulted were hyper-realistic representations of brutally severed limbs enshrined in boxes like religious relics or classical sculpture. Thek then made his most famous work in New York, The Tomb, which opened in a solo show at the Stable Gallery in 1967. It included a life-size effigy of the artist, which came to be known as the “Hippie,” a mannequin with a face and hands that had been cast in wax from Thek’s body with the help of the artist Neil Jenney. The figure was painted pale pink from head to toe, and wore a necklace of human hair and other jewelry made of mixed woven hair with gold. Pink goblets, a funerary bowl, and private letters surrounded the effigy; the fingers of the right hand had been amputated, placed in a pouch, and hung on a wall behind the figure’s head. In 1969, the “Hippie” was shown at the Whitney, under the title Death of a Hippie, and later traveled to other institutions. The work vanished at the beginning of the 1980s, but some elements will be on view at the Whitney for the first time, and it will also be represented through photographs by Peter Hujar, never before exhibited, that capture Thek creating the work in his studio.

In 1968, Thek met Michael Nickel, the director of the Galerie M. E. Thele in Essen, Germany, who invited him to show at his gallery. Thek conceived an exhibition involving chairs and “headboxes,” glass boxes that fit over the head and were constructed to be worn or performed with; they were painted in reds and pinks and adorned with hunks of meat. The culminating object was the Sedan Chair, a vehicle for one person to sit in while being carried by two others. Because much was damaged during shipping, Thek covered the gallery floor in newspaper and repaired, remade, and arranged the surviving and damaged objects. The resulting exhibition, A Procession in Honor of Aesthetic Progress: Objects to Theoretically Wear, Carry, Pull or Wave, evolved over the length of the exhibition from constructed chaos into orderly arrangement. This new process-driven form of exhibition radically altered Thek’s practice.

Thek moved from individual sculptures and tableaux, such as The Tomb, into increasingly ambitious installations. Working with a group of collaborators, including his good friend Ann Wilson and others – a group that came to be known as The Artist’s Co-op – Thek created immersive environments, similar in scope to enormous stage sets, out of a range of insubstantial materials (newspaper, sand, tissues). The artist began to describe his installations as “processions,” evoking ancient rites in observance of seasonal change as well as incorporating moments out of everyday life, and giving a sense of the works as one continuous work in progress. Thek next created another effigy of himself: Fishman, a full-body latex cast of the artist, naked and covered with fish. In 1969, at an exhibition at the Stable Gallery, the artist chose to leave the gallery bare and have the work exhibited in the courtyard, suspended in a tree. Thek made four casts of the Fishman, two of which are included in this show.

Thek created major installation works in Europe between 1969 and 1973. In keeping with the notion of the “procession,” he transported individual sculptures from one venue to the next, re-imagining them in new relationships. Although much from this period is lost, important elements from these installations, never before exhibited in the US, are included in this show, along with vintage photographs and a film depicting the works as they appeared at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, documenta 5 in Kassel, Germany, and at the Kunstmuseum Luzern.

Although he started as a painter, Thek did not make paintings (and only a handful of drawings) from 1963 to 1967. In Europe, at the end of the 60s and in the early 70s, he began to draw and paint again, using graphite, ink, and watercolor to record his surroundings, and also painting on newspaper. Along with the celestial blue images of swimmers and divers, Thek’s earliest newspaper paintings are populated by pipe-smoking dwarves, a recurring motif, isolated against aggressive red or metallic silver backgrounds. In his “island” paintings, he merges motifs with blue washes of paint on newspaper, depicting islands in the distance formed by the tip of a dwarf’s peaked cap poking through the water.

In early 1969, Thek collaborated on A document with freelance photographer Edwin Klein, an integral member of The Artist’s Co-op. A 126-page book in black-and-white, A document is devoted to photographic collages that capture the visual environment of Thek’s studio. The book was published jointly by the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam and the Moderna Museet in Stockholm to accompany Thek’s exhibitions there. It contains a shifting series of photo-collages, each built upon the same newspaper ground, their increasingly complex layers teeming with images and found objects.

Journals were highly important to Thek, and he produced more than a hundred between 1969 and 1980. Mostly written in ordinary school notebooks, they are filled with passages of self-reflection, self-doubt, and deeply personal thoughts about friends, relationships, and sex. Often Thek copied pages of writings by Saint Augustine, Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, William Blake, and others. The journals are filled with drawings in ink and watercolors, from simple comic sketches to portraits, cityscapes, seascapes, and images of the earth, fruit, and fish.

In 1975, at a foundry in Rome, Thek made an extensive series of sculptures out of bronze. The small sculptures depict mice, bowls of cherries, pipes, campfires, eyeglasses, lanterns, and other objects that Thek called The Personal Effects of the Pied Piper. Unlike the heroic works traditionally associated with bronze, these diminutive sculptures displayed a childlike quality of innocence and whimsy, and Thek seemed to regard the Pied Piper as a kind of alter-ego.

In 1976, Thek came back to New York to an art world in which he was largely unknown. He had returned in anticipation of a show at the ICA in Philadelphia, Paul Thek/Processions, which opened in 1977. In the late 1970s, he taught at Cooper Union, and also worked for a short time bagging groceries and as a hospital janitor. Although struggling financially in these years, he wrote to a friend in 1979: “I am beginning to paint again, little canvases, very little, 9” by 12”, all different styles, all different subjects, though I think a lot of Kandinsky, of Klee, of Gustave Moreau…and of Niki de St Phalle, so you can imagine that the paintings are colorful and varied.”

In the 1980s, Thek began to exhibit again, mostly small drawings and paintings in galleries in New York and Paris, work that gives evidence of the important flowering of creativity in his last years. He also created a number of installations in such venues as the Serpentine Gallery in London and the 1980 Venice Biennale. He showed The Tomb in Cologne in 1981, and did an installation at the Hirshhorn Museum in 1984. In 1985 he was chosen to represent the United States at the Bienal de São Paulo, and the following year created an installation in Ghent.

Thek had, by this time, sabotaged some of his most important professional connections and was in a precarious emotional and physical state. In 1987 he learned that he had AIDS, and by 1988, he knew that he was dying. His final installation (at Brooke Alexander) spoke to the artist’s preoccupation with death, unmistakably addressed in works that read “Dust” and “Time is a River.” A clock striking eleven bears the inscription “The Face of God” and the image of a jail window with bars pulled apart is titled Way Out. Thek died on August 10, 1988, while the exhibition was still on view.

Catalogue

The catalogue gathers art historians, curators, an artist, a conservator, and a gallerist to write a collaborative history of Thek’s career. The book includes a foreword by Adam D. Weinberg and Lynn Zelevansky, an introduction by co-curators Elisabeth Sussman and Lynn Zelevansky, and individual essays by Sussman and Zelevansky. The artist’s early Italian period is addressed by David Breslin; Whitney curator Scott Rothkopf places Thek in the context of Surrealist tendencies in American art of the 1960s; Michael Nickel provides a first-person account of Thek’s first installation, which he helped to realize; artist Ann Wilson, who worked closely with Thek and was a lifelong friend, writes of working with him in the 1970s; Thek’s inclusion in documenta 5 and the critical reaction to the show are analyzed by Susanne Neubauer; George Baker explores Thek’s outpouring of paintings in the last decade of his life; and Eleonora Nagy reports on recent conservation efforts. Historical images of objects and installations, gathered from estates and archives, represent a wider range of Thek’s works, including many that have been lost. The book, which also presents images from the artist’s notebooks, is published by the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, and Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, and distributed by Yale University Press.

Sponsorship

This exhibition was organized by the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, and Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh.

Joint support for this exhibition is provided by the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, the National Endowment for the Arts, The Dietrich Foundation, and Gail and Tony Ganz.

Major support for the Whitney’s presentation is provided by the National Committee of the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Major support for Carnegie Museum of Art’s presentation is provided by The Henry L. Hillman Fund, the Virginia Kaufman Fund, The Fellows of Carnegie Museum of Art, the Beal Publication Fund, Ann and Marty McGuinn, and Agnes Gund.