Named after a common brand of French stationary, Claire Fontaine is a “ready-made artist,” exemplifying an empty, standardized identity produced by contemporary capitalism. Her works include neon signs, sculptures, videos, light-boxes, and texts, and while her message is often militant and radical, she more closely resembles subjectivity-on-strike, compromising our ability to define it and institutionalize it.

The practice of Claire Fontaine is one that recognizes and responds to contemporary culture’s feeling of political impotency. Claire Fontaine’s motivation arises out of a history of radical protest, in particular, the Paris student uprisings of May 1968. By contextualizing her art practice in this way it function more as a reminder of when art carried an urgent political message, as much art did in the 1960s, however, that is not to invoke nostalgia for that historical moment.

Claire’s life is also a remix; a constructed identity of appropriated elements that are collected only to be redistributed.

“By exemplifying readymade and stereotypical identities imposed by social or cultural superstructures, she becomes an empty vessel. Despite her state of exhaustion, Claire Fontaine creates an art that seeks to transform political crisis into subjective emancipation. She understands that making art can’t oppose or rebel or subvert the political condition of late capitalism, so she presents herself as an artist on strike, a readymade subjectivity, a hole in the landscape through which a revolution might creep, arriving from elsewhere.”

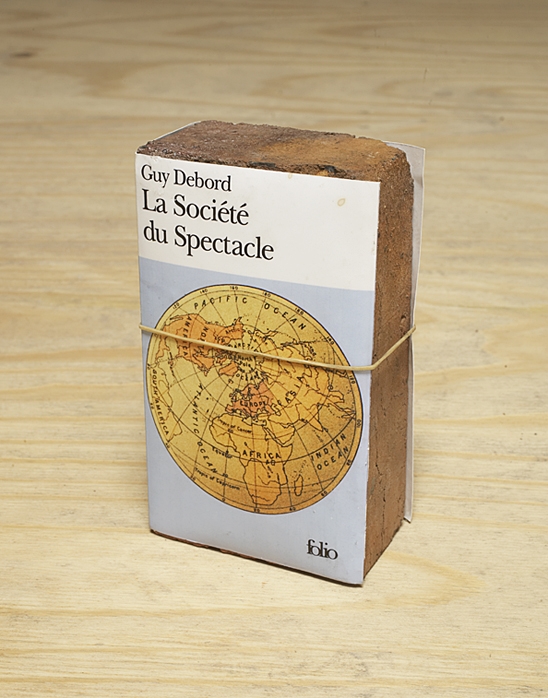

La société du spectacle brickbat, 2006,

brick and brick fragments, elastic band, and archival print on archival paper,

7×4 ½ x 2 ½ in.

Courtesy of the artist and Reena Spaulings Fine Art, New York.

“Claire Fontaine’s work asks us to reconsider our assumptions as art viewers as well as members of society and to question daily facets of life that are often taken for granted,” said MOCA Associate Curator Ruba Katrib. “Economies is a visual meditation on alternative value systems and on the contradictions connected to concepts of ‘ownership’ today, which is especially relevant in the current economic climate.”

Change, 2005.

Twelve 25-cent coins, steel box-cutter blades, solder and rivets.

Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Neu, Berlin.

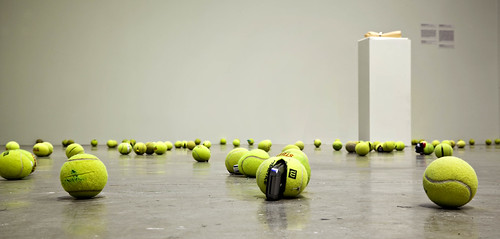

“Among the works on view is Untitled (Tennis Ball Sculpture) (2009), a floor installation comprised of tennis balls that are slit open to reveal their contents, including such items as hairpins, toffees, socks and batteries that become ‘currency’ inside prisons. The work is a response to stories of contraband entering American prisons via tennis balls thrown into prison yards,” notes Ms. Katrib.

MoCA Film Screenings

All films are free with museum admission

Wednesday, July 7, 7 pm

Reassemblage, dir. Trinh T. Minh-ha, 1982

Filmmaker, writer, poet, literary theorist, educator, musical composer, and (un/non)ethnographer, Trinh T. Minh-ha builds much of her work around the theme of the “other” (the persona one considers him/herself to be in relation to), challenging cultural theorists’ traditional notions of the subject or/subjected duality. She performed three year’s worth of ethnographic field research in West Africa the Research Expedition Program of the University of California, Berkeley. This fieldwork led in part to her first film, Reassemblage, which was filmed in Senegal and released in 1982.

Trinh’s views on traditional ethnographic documentaries are hinted at in one of her voice-overs that occurs early in the film. She states: “I do not intend to speak about/Just speak near by.” The film is a montage of fleeting images from Senegal and includes almost no narration, save for the occasional statements by Trinh, none of which attempt to assign meaning to the seconds-long scenes. Where one expects an omniscient, scientific voice to override the moving pictures in order to overlay a mapping schema of “meaning,” there is sometimes music, sometimes no sound, sometimes Trinh assigning a reality or sign to the culture it hopes to “know” by viewing a movie, she refuses to make the film be “about” something, refuses to speak about the images, and denies the hopeful observer the opportunity to record, categorize, and save an (“other”) culture. The viewer is left with a sense of disorientation, in that no meaning was assigned to any of the images in the film, and yet the viewer’s mind was constantly expecting such designations. —voices.cla.umn.edu

Wednesday, July 21, 7 pm

D’amore si vive, dir. Silvano Agosti (with English subtitles), 1984

D’AMORE SI VIVE (“One Lives by Love”) started as a film series made for television (and running about nine hours) and was later edited into a shorter feature length movie. Shot in the city of Parma, the movie examines in slow precise details the workings of love, especially among society’s rejected, physically and mentally challenged, socially excluded and otherwise loveless. It does this with a spirit of affection and not pity.

Wednesday, August 18, 7 pm

East of Paradise, dir. Lech Kowalski, 2005

Filmmaker Lech Kowalski explores his belief that struggle is “the epitome of living” in this documentary which compares the wildly different life experiences of himself and his mother. Kowalski’s mother came of age in Poland during the early stages of World War II, and after failed attempts to outrun both Nazi and Russian forces she and her family were sent to a Soviet concentration camp, where inmates were tortured, mistreated, and starved to the point where some ate their own lice in a desperate struggle to survive. Kowalski also depicts his own self-inflicted season in hell during his years on the New York City punk rock scene as he wallowed in the sordid underbelly of drug addiction, pornography, prostitution, and streetwise decadence. On both stories, Kowalski finds a message of hope and strength in the midst of almost certain peril.

MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART, NORTH MIAMI

Joan Lehman Building

770 NE 125th Street,

North Miami, Florida 33161

T +1 305 893 6211

E info@mocanomi.org