Change from Within: Kerry James Marshall Corrects the Canon:

Kerry James Marshall. Many Mansions, 1994. Acrylic and collage on unstretched canvas; 114 x 135 inches. Art Institute of Chicago, Max V. Kohnstamm Fund, 1995. Courtesy Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

“This previously unpublished text has been excerpted from an interview conducted with artist Kerry James Marshall in 2014 for the Artist to Artist film ‘Kerry James Marshall at Prospect 3.’

Art21: What about the art historical tradition drives your work?

Kerry James Marshall: Currently, the way the narrative of art history is framed, the privileged body is a white body. And because that’s the Italian Renaissance body, the Western European body, that’s where the tradition of art history as we understand it, comes from. That’s what we understand to be the ideals of beauty, ideals of grace, ideals of form, all those things. And so, a part of what I’m doing is making work that functions in those same capacities, but that centralizes the Black figure. So that’s in the paintings I make, and in a lot of the photography I do.

Art21: While we were driving around New Orleans yesterday, you mentioned how predominantly Black communities around the nation have shared situations. Could you elaborate?

KJM: The Black population as a cultural body is generally undercapitalized. And so when you find large concentrations of Black people in communities, most of those communities are undercapitalized, from undercapitalized to impoverished. And so there’s a way in which this idea of impoverishment becomes associated with the idea of Black people.

the way the narrative of art history is framed, the privileged body is a white bodyAnd so when I go from city to city, from state to state, it’s not really hard to detect where the boundaries of the traditional Black communities are, and where the boundaries of what we call traditionally White communities are, because there’s a distinct transformation that takes place across that boundary where you can see that the economic level of comfort drops, fairly dramatically in a lot of Black communities. I’m acutely aware of those transitions, acutely aware of where those boundaries seem to be.

There’s a notion that comes out of the end of Jim Crow and segregation, this idea that in part was the formulation of the Brown decision, in Brown vs. the Board of Education, that separate is inherently unequal. And you really have to look at what that means. Because what that says is not that separate is inherently unequal across the board, but separate is inherently unequal for Black people.

Because Black people in communities that are separated from what we call the mainstream don’t have anywhere near the same sort of economic capacity, the economic infrastructure, the foundation, that White communities have. So White communities could be separate and they do quite well. But Black communities that are separated don’t do so well. And so what that tends to do is reinforce the idea that there’s something inherently problematic about Black people. And you have to have an answer as to why that separation doesn’t adversely affect the White population, as it affects the Black population. And that means that you have to look at the historical relationship between these two populations in a way that I think the simple construction of that phrase, ‘separate is inherently unequal,’ doesn’t do.

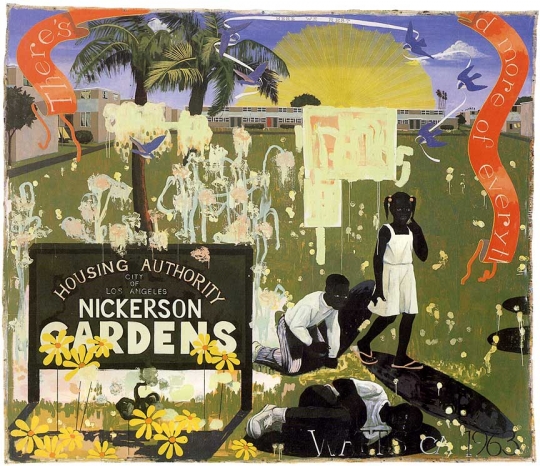

Kerry James Marshall. Watts 1963, 1995. Acrylic and collage on unstretched canvas, 114 x 135 inches. St. Louis Museum of Art, Museum Minority Artists Purchase Fund. Courtesy Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

(Via: Art21 – read full text by clicking the link above)