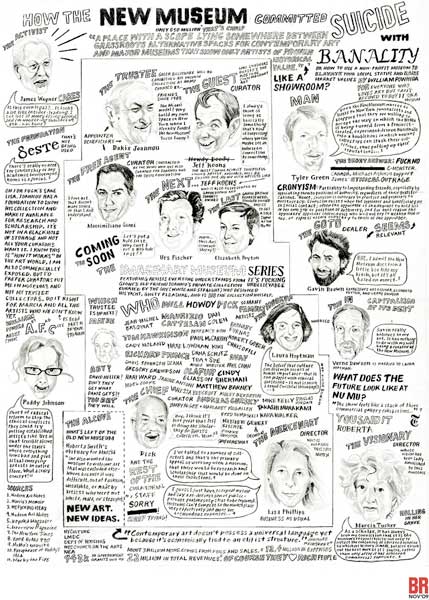

William Powhida, How the New Museum Committed Suicide with Banality, cover art, Brooklyn Rail, November 2009

(For a larger, more legible image, click here.)

———————-

The Brooklyn Rail, founded in 1998, is a scrappy, independent cultural/political broadsheet that covers issues in Brooklyn’s waterfront neighborhoods (Williamsburg, Greenpoint, DUMBO, Red Hook) from a politically progressive vantage point. It publishes poetry and fiction and reviews local developments in music, film, dance, theater and books. Most significantly, it provides passionate, detailed, idiosyncratic coverage of the NY arts scene in each and every issue, with a full roster of exhibition reviews, feature articles and long, in-depth “conversations” with artists. Under publisher Phong Bui, it has developed an essential and original voice, and is part of my regular reading list. [Full disclosure: James Kalm, who maintains an ongoing video blog here at post.thing.net, has also contributed regularly to the Rail.]

Viewable online, distributed for free at certain bookstores and alt.culture locations, and also available by subscription, the Rail has a relatively small circulation (around 7,500). Even so, it regularly engages in adventurous promotional efforts normally the province of larger publications; for example, the printing of multiple covers for certain issues to better showcase the artists and contents within.

A case in point: the three different covers of the November 2009 issue. The one I have at home features an image from a Carroll Dunham painting. I understand there was also a Helmut Federle cover. (Both artists had solo shows in NY that month and are interviewed in the November Rail.) However, it is the third cover choice I wish to address here, a b/w drawing by artist, activist, satirist and draftsman William Powhida, executed in full caricature/agitprop mode (and pictured above), in which he addresses cronyism at the New Museum in gleeful, graphic, subversive detail.

Powhida’s usual subject is the interrelationship of power and personality in the art world, and his position within that complex, morphing grid. His weapons are an enviable facility to combine recognizable portraiture and text – seemingly gleaned from years holed up reading and emulating comic books – and a tendency to manufacture fictions that deviate ever so slightly from the world we live in, yet manage to parallel, illuminate and parody this world. He has been described as a “gadfly” and a “vigilante”, and his work typically holds up a caustic, knowing mirror to the politics of price, privilege and reputation that so often regulates success and failure in our very inbred community.

“The New York Enemy/Ally Project”, Powhida’s February 2008 installation at Schroeder Romero Gallery in Chelsea – part of their “Caucus” group show – tabulated anonymous voting both for and against various entities (from Jeffrey Deitch to the L Train) that were submitted to a website established for the project and also to a ballot box located in the gallery. This conceptual, electoral parody was co-exhibited with a “killer’s row” of framed drawings, arranged along axes of the “Equivocal” and the “Absolute”, depicting the most frequently cited luminaries accompanied by representative texts taken right from the ballots.

Powhida’s large (40 by 60 inch) “Relational Wall” watercolor, at Schroeder Romero in April 2009 and part of his one man show there, presented a loose checkerboard of portraits culled from Artforum’s “Scene and Herd” and other social blogs, with accompanying captions both real and imagined. Augmented by hundreds of drawn portraits of the demimonde lifted from the navel gazing art sites, it overwhelms us with an unruly sprawl of “raw material” that gently mocks the seriousness of overarching theories like Nicolas Bourriaud’s Relational Aesthetics, as well as our insatiable magpie eye for celebrity culture, our debased appetite for rumor, gossip and innuendo, and our addiction to the trashy social networking paradigms found in sites like Facebook.

Other projects/pranks by Powhida include the parody of an Art Newspaper issue that truculently proclaims: “MARKET CRASH. Collectors abandon Miami”, illustrated with a photo of a yawningly empty art fair aisle. This was accomplished just prior to the 2008 Art Basel Miami Beach and turned out to be strangely prescient. Then, in collaboration with Jade Townsend, he envisaged Miami 2009 as an extensive Great Depression squatter camp set up in the Convention Center parking lot, complete with art dealer prostitutes and a soup kitchen line for indigent art populations, while the A-list continued to party within the building. The “recovery” has apparently not permeated all economic strata. It is a savage depiction rendered from an overhead, panopticon perspective that yields nothing in its mordant social critique to Daumier and Hogarth, let alone to Jeremy Bentham’s utilitarian formulations.

As Martin Wong was to tenement bricks and Loisaida gated storefronts, capturing their very texture, volume and palpability on canvas, so Powhida is the draftsman laureate of the torn notebook page, frequently depicting them in all their scuffed, scrunched up, disheveled and dogeared glory, sloppily taped to a wall, inscribed with scrawled lists and casual sketches, imagined even down to their horizontal ruled lines, funky, perforated holes and the half shadows they cast against the wall.

This is an uncanny ability, allowing Powhida to function like a street smart devotee of fashionable pessimism, an exceedingly dry fabulist. He creates a vaguely exaggerated, alternate universe that closely approximates the one we experience every day, tweaking it just enough to dislocate our complacency and, like William Burroughs in “Naked Lunch”, reveal “a frozen moment when everyone sees what is on the end of every fork”.

On the November Rail cover he is engaged in direct advocacy and activism, not the random, casual fantasy or humorous self promotion of earlier outings. The enormity of the New Museum’s transgression does not elicit an alternate narrative, just a clear presentation of facts, of the interlocking tentacles that reveal this insidious art world mafia. Like others who were aghast at the announcement of plans to mount an exhibition in March 2010 drawn solely from the collection of Dakis Joannou and curated by acolyte/artist/court jester Jeff Koons, Powhida seems offended by the unrepentant “insiderness” of it all, the stench of clubhouse politics, the obvious conflicts of interest. It drove him to compose this graphic scrawl of protest.

Something seems awry when four of Gavin Brown’s artists have been given shows at the New Museum over the last two years. When associate curator Massimiliano Gioni is not just a New Museum employee but has also worked directly for Joannou, and is responsible for the current Urs Fischer show (an artist represented by Brown and heavily collected by Joannou). When Joannou’s prospective curator, Koons, also has 40 works in the collection. When Joannou is a trustee of the museum, helping to raise funds, even if not contributing directly to the actual expense of exhibiting his collection. When Joannou entertains them all in his private museum on Hydra, where they get to cheer themselves silly while gorging on a dead shark. It all reeks of gratuitous elitism and feels tastelessly incestuous.

Many voices were raised in howls of execration over the New Museum’s decision, including Tyler Green in Modern Art Notes and James Wagner, but also in the NY Times and other sources outside the blogosphere. However, the great advantage Powhida has over all these wordsmiths is his ability to create pointedly powerful graphics, a potent caricature of corruption. He not only names names but also visually implicates the rascals in all their shameless, self absorbed duplicity, and depicts them as they are made to walk the perp walk before our bitter, mocking gaze. It is the propensity of graphic representation, in the great tradition of political caricature, to present an actual, tangible image for our ridicule.

Hence Koons is drawn as Howdy Doody, complete with freckles and cowlick, an amenable dummy for Joannou’s controlling ventriloquist. Brown is shown sneering: “The New Museum does look a little bit like my bitch”. Fischer brattily suggests: “Let’s put a hole in it.” Even the marriage of New Museum curator Laura Hoptman to Brown artist Verne Dawson is fronted, for our conjecture and suspicion, as an inside deal. Pompous fop Richard Flood is depicted gushing like a fuddy duddy and offering wine. “Business as Usual” Lisa Phillips is shown defending the sellout while Marcia Tucker, the visionary founder of the New Museum, who wanted her institution to “seek out the best work at its source, rather than only after it has achieved commercial exposure”, is shown watching balefully from the sidelines, and is imagined rolling in her grave.

All in all, it’s a startlingly trenchant and memorable critique, and probably one that could only be effectively delivered via caricature. If the New Museum has committed suicide with banality, Powhida wants us to consider it the banality of evil. He speaks truth to power with an effectiveness that rivals Thomas Nast’s attacks on Tammany Hall in the 1870s/80s, suggesting interesting parallels between the iconic corruption of a figure like Boss Tweed and that of jargon spouting “mercenary director” Lisa Phillips. For such courageous clairvoyance I can only applaud Powhida, and offer him a heartfelt “Bravo!”.